October, 2010 – Chris Paskach, Adam Beschloss and Steve Stein, all with KPMG [1. KPMG Forensic is a service mark of KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. KPMG and the KPMG logo are registered trademarks of KPMG International Cooperative.

The information contained herein is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavor to provide accurate and timely information, there can be no guarantee that such information is accurate as of the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future. No one should act on such information without appropriate professional advice after a thorough examination of the particular situation.

© 2010 KPMG LLP, a Delaware limited liability partnership and the U.S. member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative, a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. 21606NSS

PMG LLP, the audit, tax and advisory firm (www.us.kpmg.com), is the U.S. member firm of KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International.”) KPMG International’s member firms have 140,000 professionals, including more than 7,900 partners, in 146 countries.

SharePoint is a registered trademark of the Microsoft Corporation.

Six Sigma is a trademark of the Motorola Inc.]

Introduction

E-discovery costs are spiraling ever higher, posing a significant challenge for companies faced with litigation and regulatory investigations that require extensive data collection and review. Although market forces have driven data processing costs down as much as 90 percent since 2003,[2. For example, seven years ago, KPMG ForensicSM collected $0.25/page for producing print versions of discovery documents as TIFFs or PDF files, which meant that a gigabyte of data for e-discovery cost around $6,000. Today, these e-paper versions of documents are bundled into processing, so that data can be processed for less than $600/GB.] little has been done to address the root cause of the overall cost burden: the collection, processing, and review of too much data, much of it irrelevant or nonresponsive.

C-level executives, corporate counsel, and even judges recognize that e-discovery can no longer be conducted outside a framework of cost controls, given the excessive amounts being spent on inefficient data processing and review. Fortunately, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure now require parties to meet and confer regarding e-discovery protocols. This further encourages cost-conscious litigants to better understand their records management protocols, including backup schedules, IT systems, and document repositories. Some corporate respondents have begun to use statistical sampling and other documentable metrics to estimate the total cost of requested productions and support arguments for excessive burden and cost shifting.

The problem of too much irrelevant or nonresponsive data should be addressed first at its source – failed records and information management – and, second, by rethinking and reengineering the e-discovery response. The challenge associated with records and information management took decades to develop and could take some time to solve. This paper provides suggestions for approaching this challenge and its impact on discovery.

This paper also addresses the complexity and severity of the cost problem and suggests that a fundamental shift needs to occur in how e-discovery is executed. We describe an approach we call Smart Evidence and Discovery Management (Smart EDM), which regards e-discovery as a business process and draws on such disciplines as Lean Manufacturing (Lean) and Six SigmaTM,[3. Lean is a manufacturing process developed by the Department of Defense during WWI and made famous by Toyota in demonstrating efficiency and removal of waste in a process. Six Sigma, developed at Motorola and made ubiquitous by GE, focuses on process effectiveness. Many organizations are adopting a hybrid called Lean Six Sigma, which recognizes that processes can be both effective and efficient.] [4. Six Sigma is a methodology intended to improve performance in defined processes in relationship to an aspirational goal. Responsibility for the lawful, efficient, and effective response to subpoenas and other legal processes in a particular legal proceeding, including decisions regarding how to respond to such processes and what to produce and what not to produce in response to such legal requests, is the responsibility of counsel through their exercise of professional judgment applied to particular legal issues relevant to a specific legal proceeding, and with due consideration of controlling law, court rules, and discovery orders in effect in the specific legal proceeding. The Six Sigma processes discussed in this white paper constitute a methodology designed to measure the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of document preservation/collection, paring, processing, review, and production by counsel and is not intended to establish or advocate an independent standard by which to judge a party’s compliance with any legal obligation with respect to document collection, review, or production. Application of these processes to document preservation/collection, paring, processing, review, and production will vary from proceeding to proceeding depending on the unique circumstances of each proceeding. The methodologies expressed herein do not constitute legal advice or the practice of law, and application of Six Sigma methodologies to a litigation process is not a guarantee of any specific level of accuracy, cost-effectiveness, or financial savings. Nothing herein should be understood to be advising any party to litigation or other legal proceeding as to how the party should satisfy its legal obligations in the context of a specific proceeding or in response to a specific subpoena or document request.] to drive down costs.

Fundamental to Smart EDM is an iterative rather than linear approach to e-discovery processes that seeks to identify responsive data as close to its source as possible. What makes it smart is that on any given discovery project, these processes support learning. Using iterative techniques, such as sampling, data stratification, prioritization of custodians and data sources, and targeted collections, counsel can make adjustments as they learn more about the people, terminology, and related issues. The potential for companies is a smaller corpus of collected data, improved relevancy, reduced review time, and, ultimately, lower costs.

The Problem: Too Much Data

For many years, digital storage costs have been declining at an accelerating pace. Online storage that used to cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to purchase 25 years ago now costs but a few pennies.This precipitous drop has led companies to keep buying more storage without facing the time-consuming and expensive process of developing and implementing an effective records and information management (RIM) program. companies should be assessing their long-term return on investment of a fully implemented RIM program compared to the higher costs stemming from litigation or an investigation when no RIM program exists. These costs include storage as well as searching, collecting, reviewing, and producing potentially responsive data.

Records and Information Management: What Should Be Considered

Companies that lack an organized records management system must figure out what corporate documents exist, whether they are potentially responsive to a specific litigation or investigative trigger, and where they are located.

For many years, the save-it-all approach has led to extraordinary volumes of document stores. This has been further exacerbated by a lack of RIM programs to guide the document life cycle from creation through destruction. The lack of a proper RIM infrastructure increases the possibility of deleting a valuable record, or one subject to a hold order.

Digital information – including customer and financial databases, regulatory archives, Microsoft Office files on file shares, image files, and e-mail – is collectively referred to as electronically stored information (ESI). ESI is not paper in digital form. It represents a new paradigm with a set of technical and operational challenges that did not previously exist. A corporate employee involved in a litigation or investigation as a witness might have ESI on a work computer, home computer, thumb drive, cell phone, or PDA, as well as on an individual file share on the corporate network, departmental network, or shared work site. The challenge of determining where this ESI is located, how it can be accessed, who manages it, how it is backed up, how relevant it is, and how it can be identified and preserved requires legal, technical, and forensic competence.

ESI is far more voluminous than paper and continues to proliferate. For example, a small thumb drive can hold the equivalent of 250 banker’s boxes of paper. For corporate data, however, the notion of cheap storage is anything but when one takes into account the combined costs of power consumption, requisite redundancies, disaster recovery and business continuity, data availability, and staffing. These costs increase even further due to the inefficiencies of searching and retrieving specific documents and data from voluminous and uncontrolled data stores.

Few organizations have implemented RIM policies and procedures in a way that addresses the complexity and risks of the digital world. Ineffective policies leave content – that could have been systematically and legitimately deleted – as fair game for regulatory or internal investigations or discovery-intensive litigation. E-mail produces a wide range of sensitivities, retention requirements, and risk, but there is often no methodology, protocol, or systematic support for managing it.

As a result, corporations must seek proactive ways to create new or enforce existing content creation policies and document retention schedules (thereby allowing the permissible destruction of data) as well as seek ways to eliminate outdated and unnecessary legacy or archival data.

The Duty to Preserve and Litigation Hold

The duty to preserve data for potential litigation is a contentious legal area and produces risk for corporate defendants. Precedents suggest that once a party reasonably anticipates litigation, it must suspend its routine document retention and disposition processes and establish a litigation hold. Still, the law recognizes there are limits to what an organization can reasonably preserve.[5. Although concepts like “cost shifting” and “burden” have been applied to the production of tapes or other “inaccessible” ESI, preservation is still perceived by organizations as needing to be broad.]

The best time to consider retention-destruction tradeoffs and litigation hold execution is when developing information life-cycle policies and procedures, not after the duty to preserve takes effect. A sound RIM policy can mitigate potential risks from inadvertent data deletion, since, per Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,[6. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (December 2006) addressed spoliation “absent bad faith” in the amended rule 37(f).] the court may not impose sanctions when a party deletes or otherwise destroys ESI “as a result of the routine, good-faith operation of an electronic information system.” However, organizations and their counsel are expected to have a high level of competency in these matters. The prerequisites to obtaining such protection include clear and enforceable policies and controls relating to litigation holds and an understanding of the technology drivers.

The Demand for a Better Way

While the duty to preserve may appear to be broad, there is no reason the collection, processing, and review of data need to be equally broad. Nevertheless, these activities have historically had an unnecessarily high impact on the total cost of litigation. Having saved all its data, the organization preserves it all, the e-discovery service provider collects and processes it all, and the reviewers (billing by the hour, document or page) review it all – even though much of the material is irrelevant or nonresponsive. Over the past several years, KPMG’s analyses of selected databases containing millions of documents reviewed by attorneys have revealed that as much as 90 percent of the documents reviewed were non-responsive. In other words, the armies of contract attorneys that companies deploy for reviews are reviewing predominantly irrelevant or nonresponsive documents. Compounding this situation is the demand by those managing the review to provide the reviewers with as many documents as possible so they are never idle. This is not only inconsistent with the concept of pull from Lean manufacturing, but perhaps the epitome of what Lean and Six Sigma refer to as waste and is a key driver to unnecessarily increased cost.

In Lean parlance, the traditional e-discovery method is one based on push, where the producing party receives a request and proceeds to collect, process, review, and produce the data in a linear fashion by pushing it through the system. The opposite and more desirable method is pull, where the activity is tightly connected with demand. Creating an e-discovery process that leverages the Lean concept of pull is a challenge, and Smart EDM focuses on providing increased efficiency and productivity to reduce the risk and cost of the discovery process.

Smart EDM

Consistent with Lean manufacturing processes, the practical implications of Smart EDM are fundamental. Organizations cannot rely solely on unit cost reduction to achieve necessary savings but must instead drive savings through the smart use of process and technology to collect less data, process less data, and review less data. We discuss a number of key principles below.

EDM as a Business Process

Given the significant potential expense of e-discovery, organizations cannot allow service providers to operate carte blanche. In-house and outside counsel must understand the e-discovery process in the context of legal compliance and the current matter, and they also must be answerable to the CFO. In short, e-discovery must be comprehended operationally and financially and be subject to standards of accountability, efficiency, and effectiveness like any critical business process.

Those who are driving the discovery process still often believe that more is better, i.e. the more data, the greater the potential for discovery. However, the volumes of data kept by companies creates the potential to over-collect and consequently over-review and produce, leading both the respondent and complainant to look for a better way. A sound defensible discovery response strategy, supported by a repeatable, reproducible, and well-documented work flow, can help manage the resulting tension and costs.

Iterative Approach

As with most legal issues, a one-size-fits-all approach is ineffective. The best discovery process uses a consistent approach that considers the circumstances of the specific matter and documents the decisions involved in searching and reviewing relevant and potentially responsive documents. The choice and efficacy of particular search terms must be well thought out and tested. Failure to test search terms or sample the relevance of retrieved documents may lead to the collect too much, review too much syndrome. In one notable case for EDM, the judge makes a pointed reference to this very topic:

[C]ommon sense suggests that even a properly designed and executed keyword search may prove to be over-inclusive or under-inclusive, resulting in the identification of documents as privileged which are not, and not-privileged which, in fact, are. The only prudent way to test the reliability of the keyword search is to perform some appropriate sampling of the documents determined to be privileged and those determined not to be in order to arrive at a comfort level that the categories are neither over-inclusive nor under-inclusive.[7. See Victor Stanley, Inc. v. Creative Pipe, Inc., et al., 250 F.R.D. 251 (D.Md. 2008).]

We suggest that sampling is prudent and uses common sense throughout the process continuum we call e-discovery. Companies that use trial and adjustment, testing, measurement, and process improvement can help meet the cost and procedural challenges of e-discovery, regardless of whether it is devising litigation hold and preservation protocols or developing collection and culling strategies.

Such testing is at the core of Lean and Six Sigma. The Six Sigma DMAIC methodology (the acronym stands for define, measure, analyze, improve, and control) emphasizes a learning, iterative approach that we believe is readily adaptable to KPMG’s e-discovery process:

- Define the problem, the scope, and key issues, risks, deadlines, and [litigant] needs for the discovery review and how the legal team plans to address them

- Assess what measurement tools will be used on the project and how data will be gathered

- Analyze the data to identify potential root causes and track “as is” performance

- Develop improvement plans to address key issues

- Develop a control plan for maintaining the improved results over time.[8. KPMG Forensic, Six Sigma in the Legal Department: Obtaining Measurable Quality Improvements in Discovery Management, 2006.]

Likewise, Lean considers the use of resources for any purpose other than the creation of value to be wasteful and, thus, a target for elimination. Lean requires that processes be designed to be as efficient as possible – to reduce cycle times and eliminate wasted efforts. “Waste” is defined as any activities that are not required and do not add value to the desired result. In short, Lean is about process efficiency, and Six Sigma is about process effectiveness – both useful concepts in managing the costs of e-discovery.

The Seven Wastes of Lean

Among the Seven Wastes cited by Lean, these three are particularly applicable to e-discovery:Waste of Inventory: Redundant data sources or multiple instances of a single document add risk and cost but not value and are contrary to sound RIM policy.

Example: Multiple copies of documents on multiple systems.

Anecdotally: Large organizations store a single fact of data more than 10 times.

Waste of Overproduction: Overproduction comes in three forms: redundant systems, duplicate records, and hidden information factories, also contrary to a sound RIM policy.

Example: Redundant systems – more than one system that captures customer information.

Anecdotally: A typical mid-sized organization has 16,000 hidden information factories.

Waste of Defects: Excessive documents identified as potentially responsive by poorly defined search criteria.

Examples: Files that contain keywords but aren’t relevant or files that are resistant to processing that are discovered during processing because of inadequate data cleansing or correction.

Perhaps mistaking simplicity for speed, the traditional linear approach to e-discovery tends to define the entire EDM process at the outset before sufficient learning about the matter has occurred. Once the process for the matter is defined, teams move through their assigned steps in full batches, without the benefit of being able to adjust upstream processes according to downstream results.

For example, data preservation and collection are often completed before a full multi-level review has been performed for any sampling of the data (or custodians). Logically, how a company preserves data should affect how it collects that data, which should affect how it processes the data, and so on. Yet traditional e-discovery approaches provide limited or no opportunity for upstream adjustments that could affect downstream processes. Lean engineering refers to this as “Waste of Defects.”

An iterative approach tactically leverages technology within a strategy of smarter process. For example, a targeted collection may at first be confined to key systems and personnel, whose data is then filtered and sampled for efficacy of search terms, dates, and issues before moving on to the wholesale collection. Low relevancy rates may result in recalibrating search terms and/or reconsidering relevant custodians and the value of data from certain systems.

The approach is continuously refined from the outset. Perhaps new custodians are identified, new systems targeted, or simply more effective search criteria are identified, and then the collection process continues applying what is learned, creating a controlled process that becomes continually smarter.

The use of sampling in this manner can directly help control costs. This is simply the “measure twice, cut once” carpenter’s admonition and is a significant departure from the collect-it-all, process-it-all, review-it-all-three-times-for-privilege constraints of traditional e-discovery workflow.

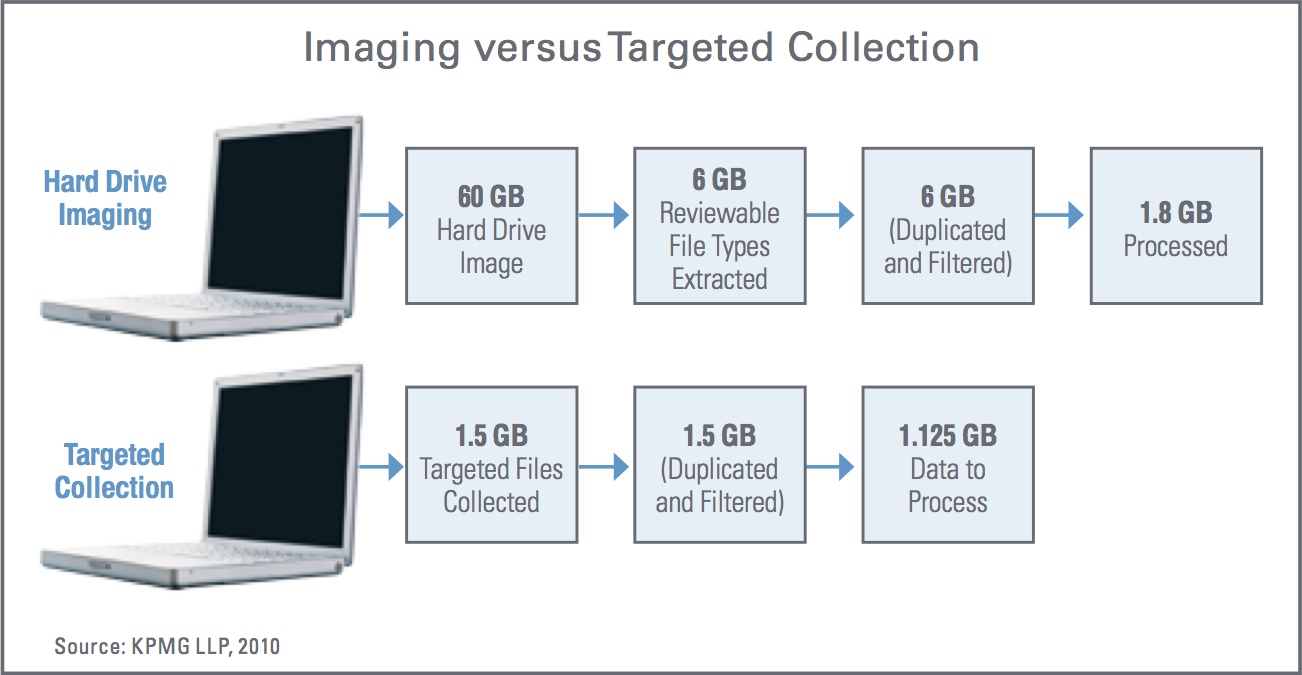

Forensic Imaging versus Targeted Collection

Traditional data collection entails full bit level imaging of custodians’ hard drives. Rather than a file copy, this method creates an exact image of the entire hard drive, including empty space, file fragments,[9. Partially overwritten files.] systems files, and programs. In other words, if a company has a witness whose laptop contains a 60 gigabyte hard drive, 60 gigabytes are collected.[10. 60GB (a typical business laptop hard drive) versus 1.5 GB on average of actual files. These numbers are based on selected project profiles and are for illustrative purposes only.[/ref]

The forensic image preserves everything, including metadata, whereas copying the drive or individual files, or simply opening a file to copy it, can alter metadata and change the evidence. Copying rather than imaging can destroy critical evidence in cases where particular metadata are central to the claim, such as the date of a memo, the last person to access it, or the exact path of where it was stored on the custodian’s hard drive. Additionally, the forensic image, in capturing deleted files, file fragments, and other data, can help uncover critical documents, or simply attest to attempts to destroy evidence. This, too, can be critical, particularly in criminal cases or where it is suspected that an employee under investigation may be hiding documents.

In cases where the full forensic image is needed to support the anticipated investigation and production requirements, this approach makes sense. However, the full drive image capture method will require the handling of significantly more data, which can lead to higher cost. Further, when an image is captured, it will typically require the additional step of extracting the imaged files for processing and the removal of all non-reviewable file types such as system files, program files, executables, etc. Only then can the remaining files be culled based on key word terms and deduplication methods.

In most non-criminal matters, deleted files and file fragments are not important considerations and do not require the deep, expensive, and time-consuming forensics that imaging supports. Even in those cases where concerns might exist – for example, suspected fraud or misconduct – it is usually confined to a limited group of key custodians. Therefore, imaging and subsequent deep forensic analysis can be done selectively.

The challenge of Smart EDM is to obtain targeted files in a forensically sound manner – chain-of-custody established, proven provenance, and metadata intact – without having to resort to drive imaging. Until recently, the necessary tools were not available. As of this writing, select service providers have a targeted collections capability as both a managed service and in support of an organization’s in-house efforts. Further, these collections can occur in coordination with interviews, greatly increasing the likelihood of finding the appropriate documents and more finely honing search terms prior to the hunt and peck of contract attorney review.

There can be significant cost savings associated with capturing files forensically via targeted collections versus full-scale imaging. In addition, targeted collection can greatly enhance the efficacy of the subsequent document review. The targeted collection technique captures at the source only potentially relevant files. Targeted collection is particularly appropriate for collecting data from network locations such as SharePoint® and other shared workspaces and document management systems, because the alternative – wholesale collections via imaging – could result in terabytes of non-relevant data. A potential downside of targeted collection is that subsequent changes in strategy, discovery of new facts, or other events could change or expand the scope of required collection, necessitating another round of collection and its attendant expense. In practice, Smart EDM employs targeted collection when appropriate, while often preserving hard drive images, particularly if there is a high risk of malicious destruction of data by parties to the case.

The Value of Forensic Interviews

A targeted collection can be done with the custodian’s participation, ideally in conjunction with the interview. In most civil litigation, where the custodian is a trusted source, the custodian can help make collection much more cost effective. With custodian involvement, testing and refinement of search terms can improve dramatically. For example, the custodian can help explain acronyms or company-, industry-, and geography-based jargon to the interviewing attorney. In addition, having a forensic technologist present can further enhance the search process in terms of keywords, dates, and other parameters.

Interviews neatly dovetail with the iterative approach: Preservation and collection can commence prior to interviews, but collection can very likely be improved and targeted as a result of information gleaned from the custodian.

Early Case Assessment

Early case assessment (ECA) is the practice of focusing discovery on the most relevant custodians at the outset in order to expand knowledge of the case quickly, followed by further discovery and learning with less critical custodians. It is a key element of Smart EDM.

Should custodian involvement be impractical (for example, high-ranking employees with limited time), unadvisable (companies will not wish to involve custodians who may have been involved in suspected wrongdoing), or impossible (departed or deceased employees), early case assessment in the form of sampling is particularly valuable. In the event a broad collection is performed, you need a methodology to quickly understand case facts, assess risk, and reduce the amount of data to be processed and ultimately reviewed. ECA can assist in this process by improving search accuracy (finding what is most likely responsive to the case issues and eliminating documents that may be responsive to anticipated search terms but irrelevant to the case), identifying key dates, assisting in determining social networks to the case at issue, and establishing key actors.

The Role of Document Analytics

Tools that are gaining acceptance include concept searching, data sampling, and search term testing, which enable the corporate respondent to document and defend preservation and collection decisions that narrow collection and production. Opinions from the bench, such as Zubalake v. UBS Warburg LLC, Victor Stanley, Inc. v. Creative Pipe, Inc., et al.; and Qualcomm Inc. v. Broadcom Corp., along with the passage of Federal Rule of Evidence 502,[11. Rule 502 addresses the inadvertent disclosure, of privileged documents in a production and provides that as long as reasonable steps were taken to prevent such a disclosure there will be no waiver of privilege. (This speaks directly to sound and defensible processes and competency.)] have recognized the need to demonstrate accountability and defensibility in the processes used to make a reasonable search for relevant and responsive documents.

The most costly components of e-discovery are often the document review and subsequent production associated with large-scale litigation. The significant interest in concept search engines, which can help make review by attorneys quicker, is fueled in part by the need to reduce this spiraling cost, as well as the need to review and produce ever-larger populations of documents and records in impossibly short time-frames.[12. As of this writing, while not yet mainstream, offshore review is gaining acceptance with organizations and some law firms as a way of reducing document review costs.]

One valuable feature of concept-based tools is their ability to group like documents together – for example, recognizing that 10,000 e-mails containing the agreed search terms are all about fantasy football pools. A reviewer can tag[13. Tagging is the association of an attorney’s decision of relevance, privilege, or issue codes to the document.[/ref] all of those documents as irrelevant in a matter of seconds, saving time and cost. Another capability is linguistic analysis, which can help locate relevant documents according to subject matter even if the documents do not include key words. Concept-based and other automated review tools have been considered effective by many and should be considered relative to the matter at hand.

Document Review

Corporations and their outside counsel should seek ways to optimize the review experience, bearing in mind that the primary way to optimize review is to produce a corpus with the highest possible level of relevancy. Nevertheless, some Smart EDM principles can be applied.\r\n\r\nOptimize in this context is the process by which an organization speeds attorney review decisions while reducing errors and inconsistent review calls among like documents. Some of the key elements of Smart EDM in the review phase are:

- Key word highlighting on the documents themselves to assist attorneys in making correct responsive or privilege calls

- Assigning batches of similar or substantially similar documents to individual reviewers

- Directing reviewers to review similar documents (duplicates, near duplicates, or e-mail strings) even if those documents are not in their individual batches

- Having an experienced project manager on staff to oversee that reviewers are using all available tools.

Conclusion

Nonexistent or ineffective RIM programs threaten to seriously hinder traditional e-discovery processes, despite recent technical improvements and cost-savings.The time has come for a new way.

By combining RIM sophistication with Smart EDM, potential respondents can reduce the amount of data they collect, process, and review, thereby increasing the possibility of emerging from litigation or an investigation financially intact.

The essence of Smart EDM is to view e-discovery as a business process and take an iterative approach to collection, processing, review, and production. These two concepts, with Six Sigma and Lean underpinnings, contrast starkly with traditional approaches to e-discovery.

As litigation costs continue to skyrocket, litigation is becoming untenable to many companies. Still, settling may be unpalatable or contrary to long-range business interests. The economics of e-discovery demand a better way. With Smart EDM, companies may now have one.

About the Authors

Chris Paskach is the national service network leader of the Forensic Technology Services practice for KPMG LLP. He coordinates the services and technologies offered by KPMG’s Forensic Technology Services team, including those provided from KPMG’s Cypress Technology Center (CTEC). Chris is a member of The Sedona Conference Working Group 1 and The EDRM Advisory Council. He was also a member of the Working Group 1 drafting committee for the recently published Sedona Conference Commentary on Achieving Quality in the E-Discovery Process, May 2009. Chris can be reached at 714-934-5442 or cpaskach@kpmg.com.

Adam Beschloss is a director in KPMG’s Forensic Technology Services group and leads its Evidence and Discovery Management (EDM) team in New York. Adam has 10 years’ experience in the legal industry developing discovery and critical document workflow approaches for service provider, law firm, and OGC clients. He has served as an advisor for implementing investigation and litigation workflow on behalf of OGC of FORTUNE 50 clientele, and has substantial experience leading and coordinating e-discovery engagements as engagement manager supporting large-scale complex litigation. Adam can be reached at 212-954-2948 or abeschloss@kpmg.com.

Steve Stein is a managing director in KPMG Forensic’s Evidence and Discovery Management group in Chicago. He has worked with corporations and law firms to scope, implement, and manage workflow for the retention, acquisition, search, review, and production of electronically stored information. Steve has served as a technical advisor on behalf of clients at federally mandated meetings and conferences. He also has managed effective approaches for backup tape restoration, remediation, and computer forensics. Steve can be reached at 312-665-3181 or ssstein@kpmg. com.

About KPMG’s Forensic Technology Services

KPMG’s Forensic Technology Services (FTS) group provides end-to-end electronic discovery services that offer measurable quality and review-team efficiency. In addition to digital evidence collection and computer forensic services, KPMG provides advanced discovery management, data conversion, and data repository services leveraging our Discovery RadarTM suite of applications and CTEC capabilities and infrastructure.

Disclaimer

Unless otherwise noted, all opinions expressed in the EDRM White Paper Series materials are those of the authors, of course, and not of EDRM, EDRM participants, the author’s employers, or anyone else.