Updated November 3, 2010

Aim: In the identification phase the legal team develops and executes a plan to identify and validate potentially relevant ESI sources including people and systems.

Introduction

See also EDRM Identification Standards.

Identification is used to identify potential sources of relevant information. These sources may include business units, people, IT systems and paper files. Learning the location of potentially discoverable data is necessary to issue an effective legal hold. Identification should be as thorough and comprehensive as possible. Conduct interviews with key players to identify what type of records they have that may be relevant. Interviews with IT and records management personnel may be used to identify how and where the relevant data is stored, retention policies, inaccessible data and what tools are available to assist in the identification process.

The scope of data potentially subject to preservation and disclosure may be uncertain in the early phases of a legal dispute. The nature of the dispute itself and the individuals involved may change as the litigation progresses. The identification team should anticipate change and have a procedure in place for capturing any newly identified information. Identification requires diligent investigation and analytical thinking. The very short time frames typically imposed by litigation are not likely to be met without an internal champion who can authorize and direct internal experts and custodians to treat identification as a business priority.

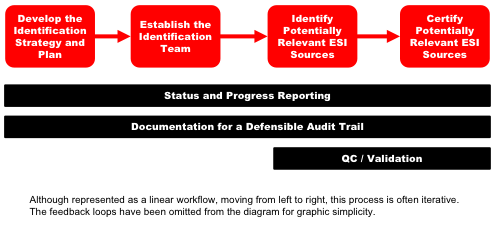

In this guide we will discuss the many factors to be considered for identifying potential sources of relevant information. We will do this in 4 main phases: Develop the Identification Strategy and Plan, Establish the Identification Team, Identify Potentially Relevant ESI Sources and Certify Potentially Relevant ESI Sources. Additionally we will identify processes for Status and Progress Reporting, Documentation for a Defensible Audit Trail and QC/Validation. At the end of this guide you will find lists of risks and recommendations.

Our focus will be on electronic data, although some issues also are pertinent hard copy data. Throughout, we will introduce emerging technologies and trends.

1. Develop the Identification Strategy & Plan

“Identification” is a two-sided coin. One side is “identifying” key players, custodians, locations of data and traceability of data to individuals and departments. The other side is “identifying” key people involved in the discovery project management and enforcement of the litigation hold, such as corporate legal counsel, personnel from IT and records management departments, outside counsel and discovery consultants and service providers. The identification strategy is paramount.

Courts, state and federal legislatures, and government regulators have developed rules concerning how organizations identify electronically stored information (“ESI”), particularly for purposes of civil and criminal proceedings, investigations, and audits. One of the principal rules is that organizations have a duty to take reasonable steps to identify and preserve relevant ESI when a litigation or investigation is reasonably anticipated or pending against them. Underlying this duty to identify and preserve ESI, an organization must be able to locate and preserve relevant ESI in a timely manner.

In this environment, organizations are expected to develop appropriate ESI management protocols and be compliant with those rules. The Offices of the General Counsel and Information Technology (IT) are typically held accountable for the enterprise-wide ESI management practices and generally depend upon the support of leadership in other areas of the organization to effectively execute these practices. These stakeholders are expected to take reasonable steps to ensure that all data potentially relevant to a matter or inquiry are identifiable. As such, developing a strategy and executing upon a defined, defensible process for identification is critical.

Organizations need to have the ability to identify the particular systems that are likely to be subject to preservation and disclosure requirements in investigations and litigations. Being proactive and gathering timely information about high risk systems will enable them to meet the expectations of the courts and regulators. Organizations should take steps to expand their current understanding of their information systems to include what systems are in operation, how those systems or applications are related, where those systems are housed, which organizations those systems support, who key contact personnel are for those systems, and other information which could potentially be necessary for timely and adequate preservation and disclosure in litigations and investigations. This is commonly referred to as “Data Mapping”.

1.1. Data Mapping

You can’t secure it if you can’t find it. An essential component to a successful electronic discovery project is an accurate picture of the target company’s data sources. It is important to keep in mind that all company information technology infrastructures are not created equal. The hardware and software deployed to accomplish commonplace tasks such as managing company e-mail or creating data backups, varies widely from organization to organization. Indeed, it likely varies within the target company if the timeframe in question is broad enough, or if the company is widely distributed in various geographic locations.

This identification process implicates many types of servers with active and dynamic data (e.g. file servers, collaboration servers, e-mail servers) and many interrelated data management systems (e.g. document management systems, financial systems, disaster recovery and backup systems). This includes servers responsible for general company data, as well as user specific data, such as user home directories or departmental shared directories. It also includes the myriad of devices that users employ to utilize that data, including desktop computers, photocopiers, calendars, Instant Messaging (IM), text, PDA’s and cell phones, smart phones, and memory cards. Lastly, it implicates inactive data archives on various media such as hard drives, servers, recycle bins, tape backups, flash drives, CD-ROMs and DVDs. All of this is further complicated by the fact that legacy data, potentially across all these categories, may exist from previous company systems within the relevant time period. The necessary hardware, software or technical expertise to access such legacy data may no longer exist within the target company.

1.2. Prepare the Identification Plan

Developing your identification plan depends on several factors:

- Availability of tools that help identify individuals and data custodians who may be in possession of information potentially relevant

- Known key players, keywords and data ranges

- Relationships of data custodians

- Ability to conduct keyword searches, date ranges or other filters

- Availability of a data map and knowledge of systems that contain electronically stored information (ESI)

The Identification Plan lays out the tasks and tools you will use to identify potentially relevant ESI sources. Even in the simplest cases a plan can ensure that all the bases are covered to demonstrate a defensible process.

Starting with a plan will not only ensure that all bases are covered but will also provide you with information for budgeting and managing the process. Additionally, clear assignments and expectations can be set for determining who is responsible for each task. This plan should be flexible so it can be modified as things develop in the case. It is likely that tasks may change and additional items will be added once you begin to execute the identification plan.

Start by making a list of individuals that may possess or have knowledge of relevant information. The initial list of individuals may be identified by the opposing party or through the legal department, records manager, Human Resources or business units involved in the matter. Also note how each individual was identified. Were they identified by the legal department, business units or IT and records management? Making a list will serve as a foundation for future tasks associated with each individual.

Determine if identification should be based upon department, geography, job function or other criteria, such as date ranges, domain names, entity, etc. Identify which departments and/or divisions within the organization may responsible for subject matters identified in the document request. For example, responsibility/ownership of specific projects or contracts should be tied to the applicable departments and employees.

Next, identify the type of individual. Some individuals will be resources for locating information such as IT and records managers while others are actual custodians in the case. Identifying these at the outset will assist in identifying the type of questions that may be appropriate for the individual. For the custodians, identify those that are key vs. non-key. Also identify what type of records you think they will have. The approach you take may differ depending on these factors.

For each individual, document how you plan on identifying relevant information. Will you interview everyone on the list or do you plan on using a survey for some of the non-key witnesses. In some cases you may plan on a survey and end up conducting an interview based on the responses but as mentioned above the plan can be modified as things develop.

Ideally you have template interview questions and surveys. If so, identify which set of questions or surveys you plan on using for each individual. If you do not have standard templates this is a perfect opportunity to develop them. Create the list of questions you plan on asking various types of individuals based on the information you have recorded. You may have different questions based on the type of individual and for key vs. non-key individuals. Questions might even vary by business unit.

Finally, consider adding additional fields to your list to track the progress of the identification process. In most cases you will want to know who is accountable for interviewing or surveying each individual, when it is scheduled, when it is completed, what was found (in general) and other individuals they may have identified.

A sample template is below for reference.

| Identification Plan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name: | Bill Blue | Randi Red | Gretta Green | Wendy White | Bob Brown |

| Title: | Manager | Secretary | Engineer | IT | Records Manager |

| Type of Source: | Custodian | Custodian | Custodian | Resource | Resource |

| Key or Non-Key: | Key | Key | Non-Key | N/A | N/A |

| How Identified: | Paul Pink, Director | Bill Blue, Manager | Bill Blue, Manager | Bruce Beige, GC | Bruce Beige, GC |

| Type of Information Expected: | Contracts/Agreements, E-mail | Contracts/Agreements, E-mail | CDA Drawings, E-mail | Data Storage and IT Policies | Records Storage and Retention Policy |

| Investigation Plan: | Interview | Interview | Survey | Interview | Interview |

| Question Set #: | Doc#93256789 | Doc#93256789 | Doc#789123009 | Doc#921234987 | Doc#922234991 |

| Assigned To: | JKB | JKB | PEB | STR | LPN |

| Scheduled Date: | 1/15/2011 | 1/17/2011 | 1/1/2011 | 1/5/2011 | 1/6/2011 |

| Date Complete: | |||||

| Relevant Information: | |||||

| Other Individuals: | |||||

| Follow-up: | Possible interview | ||||

Once you have identified the approach, the standards and a method for managing the identification process you can begin assigning these tasks to the appropriate members on your team.

2. Establish the Identification Team

The Identification team is essential and has overall responsibility for identifying the key players, data custodians and data relevant to a matter. This team is accountable and responsible for various aspects of the identification process and may be consulted with as necessary. The Identification team should consist of one or more of the following individuals:

- Corporate legal counsel – may have e-discovery response plan which includes identification plan, can assist in identifying potential business units and systems with relevant information, can be used to communicate legal hold information

- Outside counsel – should understand the identification plan and ensure it is defensible

- IT personnel – can identify and describe auto-delete systems and back-up rotations, can identify all of the locations where data may be stored, may also identify systems containing relevant data that weren’t identified by business units, can provide computer policies including back-ups, data use/storage and hardware, may have asset management system to manage hardware

- Records management personnel – can provide information regarding how/where information is stored and records retention/destruction policies and schedules

- Data custodians – can tell you what systems they use that may contain relevant data and where they may store relevant data

- HR personnel – can provide lists of employees and employment information (business unit, position, hire/term date, etc.) used to identify potential custodians

- Business leaders – can identify systems used by business unit, can identify individual employees within unit who may have relevant information, can be used to communicate legal hold information

- Service providers/Discovery consultants – can offer expertise in identifying location of relevant data

This team will execute the Identification Plan.

3. Identify Potentially Relevant ESI Sources

3.1. Identifying Key Witnesses and Custodians

The typical corporate infrastructure includes a broad population of users representing the organization’s everyday routine. Not everyone in a company may be relevant to a particular litigation, but the IT organization, which is designed to support an entire infrastructure, will be. In many cases, key players must be identified by opposing parties. Of course, the requesting parties don’t want to limit a search that may result in responsive data being missed. It has been traditional to have the producing party decide who the key players are and target them for specific collection. The meet-and-confer conference held early on in the discovery process can be used to identify who the key players are and what kind of data can be expected from each.

3.2. Determining Key Time Frames

Review the relevant pleadings and discovery requests to determine the relevant time period to the matter. Use these dates to assist in locating and culling relevant data.

3.3. Keyword Lists

As you interview each potential custodian, ask them about particular jargon or acronyms that may have been used in correspondence, reports, etc., to ensure that all relevant data is searched. Compile a keyword list to be used during the collection, processing and/or review of the data.

3.4. Identifying Potentially Relevant Document and Data Types

Are only certain types of data relevant? Can all other types be excluded from the search? Document types are another item for negotiation during the meet and confer process.

While identifying where data is physically stored on the network it is important to identify the type of data that should be found at each location such as e-mail, Microsoft application documents, Adobe Acrobat documents, proprietary application files, etc. Certain data types will warrant more detailed inquiry so that the best collection plan can be determined.

During the identification process, potential custodians are interviewed to determine if they are in possession of relevant documents or data. These interviews in turn may lead to the identification or elimination of other key players or possible locations of relevant data. Review the litigation hold letter throughout the identification and collection process to ensure it references any newly identified personnel, locations, relevant time periods, etc. discovered during the interview process. See “Preservation Guide” for more information on litigation holds. By the same token, if a meet and confer was held, details such as the scope of the requests, timing to comply, method of production and cost considerations should be worked out. Become familiar with these agreements and keep them in mind throughout the identification process.

It is also important to understand the company’s current upgrade path and the schedule for any upgrades, data migration, or data consolidation that might affect the ability to utilize currently available data, or recently archived data during the course of the litigation.

3.5. File Storage

Does the corporation store user created files in a document management system that profiles and categorizes documents on particular servers? If so, what is the name and version number of the system? Is utilization of the system required of all departments and personnel? Can the system be bypassed? What enforcement mechanisms are in place to ensure that documents are stored correctly? Can the system create audit reports of access, edits, versions or copies of documents stored within it?

If the corporation does not have a DMS, where are files stored? Are there file servers in various locations? Is there a Storage Area Network (SAN) where data from multiple servers is centrally stored. How is the data organized? Do the servers have departmental or personal shares?

Do users have the ability to store files on their local workstations or laptop hard drives? If so, is there a requirement to store these files in a specific location on the hard drive? Is this requirement followed?

Is there a policy for recycling servers or user hard drives? What happens when someone leaves the company? Are any PCs or servers that may contain relevant information currently pending recycling? Is there a policy for failed hard drives? Are there any that may contain relevant information from which a forensic recovery might be possible?

Can users store files on removable media (floppies, CD-ROMs, DVDs, zip drives, thumb drives, etc.)?

3.6. E-Mail Systems

What types of electronic mail servers are deployed within the organization? Seek specifics regarding hardware, operating system, software name and version, location of servers, persons responsible for administering the mail system, etc. If there aren’t any e-mail servers, what system are they using? Pop3 or SAAS? Where is the data stored and what client software is used to access it. Determine the location of mailboxes of relevant custodians. Is there email management software in place that has “janitorial” functions such as deleting or archiving e-mail through an automated process? What are the server retention/archive settings? What is retention policy? What happens to an employee’s e-mail, mailbox and e-mail account when they leave the company? Are mailboxes restricted in size? Do e-mail stores have encryption or password protection? Does the organization allow remote access to email, and if so, by what means? Can users archive e-mail outside the mail server on their local drives, other network locations, or removable media? Is e-mail stored on user’s hard drives? Is journaling turned on? Is any information cached in the e-mail gateway that may be relevant? Is any type of e-mail archiving being used?

There are numerous e-mail systems and even more settings that can impact where e-mail information is stored. Be sure to ask all of the questions necessary to identify relevant e-mail.

3.7. Determine Relevance of Backup Media, Retired Hardware and Disaster Recovery Systems

Back up tape systems were created as disaster recovery systems for a catastrophic event. They are meant to restore an entire system or systems after a cataclysmic event and not to restore an email from a single user. Many large corporations can be managing terabytes of documents and email on a day to day basis. This is the equivalent of billions pages of reviewable documents.

Tapes are almost an ideal storage medium as it is capable of storing high capacities of information for a relatively low cost. Physical size is easy to place and they can be stored off-site for enhanced data security.

Back up tape mechanism could be different for different organization. It is very important to understand your organization’s backup tape mechanism to make sure all the data is available at any given time and at the time of Legal Hold, no back up tape is being overwritten.

Interviews with information technology personnel will provide the details necessary to understand their backup procedure and schedule. Find out how the backups are performed, how often they are performed and where the tapes are kept. Obtain a list of all servers that are actually backed up. Does their backup process perform a full system copy each time or are incremental backups performed? Determine if there have been any system changes during the relevant time period. Did the company change their hardware or software? Did they start using a third party service? Are individual hard drives backed up?

A few of the backup strategies most organizations follow Include: Grandfather-Father-Son, Six-Tape Rotation, Tower of Hanoi, etc.

For most of the strategies, there are sets of tapes, which are backed up daily, and then there are sets to take weekly and monthly backups. For most organization, the daily and weekly tapes are rotation tapes that are rotated (overwritten) next week/month after the previous week’s/month’s data is backed up on weekly/monthly tape.

As part of Identification, understanding of the backup tapes strategy plays important role to avoid capturing too much of the data or missing some data. For a particular case matter, where a particular custodian’s data need to be targeted from the backup tapes, the daily backup tapes could become more useful vs. the monthly backup tapes.

Still, since live data keeps changing, a daily back up tape could have some data, which is then deleted from the live environment and does not make to the weekly or monthly back up. This kind of situation is very important to understand to make sure the tape rotation is stopped at the time of a case matter ESI identification.

A company may cease recycling backup tapes when a hold is initiated. This can be problematic because it defines the disaster recovery system as the method of preserving data. As discussed above, it can sometimes be problematic to restore data from backup tapes in a timely and cost-effective manner. An alternative is to pull specific backups if they may contain relevant information that is not on the active system. Understanding the system in detail is key to developing a preservation strategy. See the EDRM “Preservation Guide” for more information on preservation strategies.

3.8. Legacy Systems

Consideration must be given to any prior systems that were in place to handle information during the relevant time period. It is common for companies to migrate between technologies as more desirable means to accomplish a company’s objectives are developed and come to market. Legacy systems may be incompatible with the current hardware or software in place. The hardware and/or prior versions of the software may no longer exist within the company to restore this data. Similarly, the individuals with knowledge of operation of these prior systems may have left the company. An identification of these resources is essential in order to understand whether the data is reasonably accessible and the extent to which third party vendors will be required to reach historical data if this is deemed necessary.

3.9. Cloud Computing or Third-Party Systems

It has become increasingly popular to store data in locations away from the primary business for security, cost-efficiency or disaster recovery purposes. These sources should be identified if they house data potentially relevant to the dispute. Examples of this include cloud computing, SaaS, off-site company storage facilities, co-location data centers, third party data warehousing, or third party tape storage (i.e., Iron Mountain, Recall, etc.).

If a cloud solution is being utilized to store potentially relevant information you will likely need to put a 3rd party hold in place. Additionally you should interview the 3rd party provider to identify where and how the data is stored. 3rd party providers are likely to have back-ups of the data so it is important to ask about retention and rotation of back-ups. You should also ask what their policy is for swapping out servers. You may find out that there is an old server sitting around that contains relevant data. Another area to consider is whether the potentially relevant information is comingled with any other data. Finally, ask where the servers are located. This information will identify if there are any challenges in collecting data from another country.

3.10. Additional Data Sources

Beyond the servers in the organization, there are many other devices and options that provide the ability to store active data. Include questions when interviewing the client IT about all places where relevant files may be stored.

- Digital voice mail stores and/or VOIP(voice over internet protocol) stores. Where is voice mail stored? Are their limits based on size or time? Does the company phone switch maintain relevant records?

- Portable Devices include Personal Digital Assistants (Palm Pilot, Blackberry, etc.) and cell phones. How do PDA’s synch with the server? Could there be e-mail on the PDA that isn’t on the server? What about attachments? Instant messaging or voice mails? Do users cell phones cache business data such as text messages or e-mails?

- Information on company intranet/extranet and the ability to export from these sources. Is there relevant information stored on an intranet or extranet? What type of information (documents, calendars, notes, etc.)? Is this data stored internally or in the cloud? Can users download copies of this information?

- Employee use of their home computers for business matters and the storage of business information on them. How is remote access handled? Can users download files to their home computer when connected remotely? Do any of the relevant custodians work from home?

- Instant Messaging. Is IM stored anywhere? Could it be in logs, on servers or on portable devices? What about back-ups?

- Are there any collaborative systems (e.g. Groove Technologies, eRoom, SharePoint) that might contain relevant data?

4. Certify Potentially Relevant ESI Sources

All the efforts and results for potentially relevant ESI sources should be verified by the eDiscovery team head or the Counsel involved.

The efforts and results include, and not limited to, the disclosures, requests, responses and/or objections. All types of the ESI sources that have been searched for the ESI shall be mentioned. If any known ESI source could not be searched or targeted for, it must be specifically mentioned with the detailed reasoning behind it.

In addition, certification process involves proper Litigation Hold mechanism used to preserve the data. The proper authority also has to certify what process and tools have been used for the Litigation Hold purposes for various hardware, network sources as well as method of notification and preservation for the data with the Custodian, such as a laptop/desktop or various media. See Preservation guide for more details on legal holds.

The identification process should be reasonable and defensible. Creating documentation to certify the processes, tools and methodologies used to identify potentially relevant ESI sources may provide assistance if the question of defensibility come into play. If no documentation is created to certify what steps were taken and it is discovered down the road that a potential source was missed it would be difficult to demonstrate that the identification process was reasonable and defensible.

5. Status and Progress Reporting

Status and Progress Reporting are two important elements to the process allowing management the ability to analyze projects on a case-by-case basis. IT and/or selected individuals may provide reports with schedule according to item 2 above. Stakeholders and management likely decide what information is necessary? Does Document Management System provide reports? If so, what details does the software provide? What are the policies for the reporting process?

Implementing Status and Progress reporting will likely locate errors & omissions, duplication, issues, and obstacles that may impair projects from being on-time and on-budget.

6. Documentation for Defensible Audit Trail

Documentation of the identification process can be very valuable throughout the case when questions arise regarding additional sources of information. More importantly it can be used to demonstrate the identification process was defensible should it come under question.

Consider collecting the following documents for the case file at the time there is a triggering event. Many of these documents may be revised routinely and it may be important to determine how things were at the time a hold was placed. Before asking for these documents be sure you understand what they are and how they will be useful in the case. Some network diagrams can be very complex and will not provide you with the information you need.

- Records Retention Policy & Schedule

- E-Discovery Response Plan

- Computer System Lists, Maps or Diagrams

- IT Policies that may impact discovery

- Organization Charts

As the identification process is conducted it is important to document the process to show it is reasonable and complete. The following documentation should be created and maintained with the case file:

- Identification Strategy

- Identification Plan (see template under section 2)

- Interview Questions

- Interview Responses/Memoranda

- Surveys/Questionnaires

- Interview Logs

- Any information that demonstrates how the identification process or assumptions were validated

7. QC / Validation

As the last step in the Identification process, review the following to make sure there is no hole left in the process:

- Since all the data is susceptible to deletion, make sure proper Litigation Hold has been put in place and applied for

- Emails are almost always get targeted, make sure that all the email sources (Email Servers, personal computers, PST/NSF file sources, etc.) have been included in the relevant ESI sources

- Make sure all the communications and decisions have been documented

- Make sure that proper documentation has been make for available policies and procedures regarding document retention/destruction, data backup and tape recycling, etc.

Last but not the least, before the identification is marked as being complete, for now, a team meeting that should include all the key players involved in the identification process, should be held and all the individuals and their processes should be accounted for.

The minutes of meeting should be documented properly and preserved for the life of the case. Periodically review identification strategy and plan. You may want to have one person oversee and validate that all custodians were contacted and all the documentation regarding identification is in the file. This individual can also ensure that all follow-ups on interviews were handled and identify any inconsistencies or gaps in the information.

8. Recommendations

- Develop an identification plan so the process is repeatable and defensible. Even in the simplest cases a plan can ensure that all the bases are covered.

- Include clear assignments and expectations in the plan.

- Create a list of systems or possibly a data map to provide a centralized listing of what type of data you have and where it is stored. If complete this list can be used as a starting point in every case.

- Start by making a list of the departments and individuals who may have knowledge of information relevant to the case.

- Include key information in your plan about each witness and information regarding your plan for investigation.

- Develop standard interview questions and survey forms that can be used in multiple cases.

- Consider and identify all appropriate individuals on the identification team and clearly define responsibilities.

- Gain insight into your company’s application portfolio, systems, data flow and capabilities, understand how they map to business units and keep this knowledge current to identify potentially relevant ESI sources.

- Determine what files and systems may contain relevant data (e-mail, user created files stored on file servers or in document management systems including SharePoint, databases, instant messages, voice mail, etc.)

- Determine key time frames, keyword lists and data types to determine what data needs to be collected.

- Ask about the current upgrade path and discuss requirements for any future upgrades, data consolidation or migration.

- Determine all data storage sources where relevant data may be stored (local computers, servers, cloud, back-up, external media, portable devices, home computers, intranets, extranets, etc.)

- Determine if there are any auto delete systems, data purging or if the relevant data sources are overwritten in the ordinary course and develop a plan to preserve this information.

- Review and revise litigation hold if needed after identifying potentially relevant ESI sources.

- Create documentation to certify processes , tools and methodologies used in identification process to demonstrate the process was reasonable and defensible.

- Provide status and progress reports regarding the identification process on a regular basis.

- Collect documentation related to the identification process such as records retention schedules, response plans, system lists, maps or diagrams, organization charts and IT policies that may impact discovery.

- Create and maintain documentation throughout the identification process to demonstrate a defensible process. Documentation may include identification strategy, identification plan, interview questions, surveys, interview responses and memoranda, interview logs, etc.

- Create Q/C and validation plans throughout the identification process to ensure it is thorough and defensible.

9. Risks/Analysis

- Failure to develop an identification plan may result in a process that is chaotic, undocumented and difficult to defend.

- Failure to identify clear assignments and expectations in the plan may result in steps being inconsistent, overlooked or missed.

- Failure to have a list of systems or data map will increase the cost of the identification process by re-inventing the wheel on each case.

- A list of systems or data map must be kept up to date. Failure to do so may result in missed information.

- Failure to list departments and individuals who may have knowledge of relevant information and log identification results may result in missed information and it will be difficult to determine what was done, when and how down the road.

- Failure to develop standard interview questions and survey forms will increase the cost of identification by re-inventing the wheel on each case.

- Failure to include the appropriate individuals on the identification team may result in failure to identify relevant data.

- Failure to identify relevant sources of information may result in being unprepared and spoliation of data.

- Failure to determine what files and systems may contain relevant data, time frames, keyword lists and data types may result in unnecessary preservation

- Failure to ask about the current upgrade path, future upgrades and data consolidation or migration plans may result in spoliation.

- Failure to determine and understand data storage sources where relevant data may be stored may result in missed data or spoliation.

- Failure to identify auto delete systems, data purging or if the relevant data sources are overwritten in the ordinary course and develop a plan to address this information may result in spoliation.

- Failure to review and revise litigation hold if needed after identifying potentially relevant ESI sources may result in an ineffective litigation hold.

- Failure to create documentation certifying the identification process may make it difficult to demonstrate down the road that the process was reasonable and defensible.

- Failure to provide status and progress reports regarding the identification process on a regular basis may result in increased cost and budget overruns.

- Failure to collect documentation related to the identification process such as records retention schedules, response plans, system lists, maps or diagrams, organization charts and IT policies that may impact discovery may make it difficult to show how the organization looked at the time the hold went into place.

- Failure to create and maintain documentation throughout the identification process may make it difficult to demonstrate a defensible process down the road.

- Create Q/C and validation plans throughout the identification process to ensure it is thorough and defensible.