[Editor’s Note: EDRM is proud to support the advocacy of our Global Advisory Council leaders, project contributors, trusted partners and independent bloggers, and takes no official EDRM position on rule or legislative changes without the assent of the EDRM Global Advisory Council.]

This is the conclusion of the blog, The Right to Privacy in Modern Discovery: a review of another great law review article. See here for Part 1 and Part 2. This blog series considers the interplay between privacy and civil discovery as discussed in the law review article by Professor Allyson Haynes Stuart, entitled A Right to Privacy for Modern Discovery, 29 GEO. MASON L. REV. (Issue 3, 2022).

Part Three wrap up the series with longer than usual concluding remarks. Professor Stuart’s important article and insights are tied to efforts of the electronic discovery community. I plea for further efforts and make some specific suggestions, including a proposed change to Rule 26(b)(1) to add privacy as a proportionality factor. Evidence Rule 502 may also need to be revised. Vendors should also focus on new technological solutions. The need to address the problem of discovery privacy is urgent. EDRM, The Sedona Conference®, the Advisory Committee on Civil Rules, and other important legal groups need to focus on this now, not later.

Conclusion

I look forward to hearing much more from Allyson Stuart in the years to come. We need to begin a new dialogue on how to treat confidential information in civil discovery. Judges and private practitioners like myself are facing these issues every day. Professor Stuart’s article is a good step towards finding a practical solution. A Right to Privacy for Modern Discovery, 29 GEO. MASON L. REV. (Issue 3, 2022). This is the first scholarly article I have seen focused solely on privacy in civil discovery, as opposed to the many legal articles on privacy in general, or ones just focused on attorney-client privilege, or international privacy. That is one reason her new article is so important.

I am impressed by Professor Stuart’s points and suggestions, but would like to hear more comments on her proposed framework. I hope her article and this blog series starts Sedona-style dialogues on the subject in many fora, not just The Sedona Conference®. See eg. The 13th Annual Sedona Conference Institute Program on eDiscovery: Protecting Privacy, Confidentiality, and Privilege in Civil Litigation. This March 2019 Sedona Conference event in Charlotte was co-chaired by the well-known, retired Judge Andrew Peck and Andrea L. D’Ambra and had a great faculty. I would like to hear Sedona’s input concerning Professor Stuart’s article and proposals. Also see the 2018 publication, The Sedona Conference Data Privacy Primer. This Data Privacy Primer was a project of The Sedona Conference® Working Group Eleven on Data Security and Privacy Liability and was first published for comments in January 2017. Much has changed since then, not only the shock and disruption of Covid and politics, and the ever accelerating advance of personal technologies and social media, but especially the recent, radicalizing shock of Dobbs.

Let’s hope that all serious students, practitioners, judges and scholars of the law, including Sedona, will revisit the discovery privacy issues and hear from the next generation of experts like Professor Stuart. This time I suggest groups narrow their focus to discovery as a sub-set of privacy. Let’s look at the trees, not just the forest. That is what working lawyers like me really need right now. Sedona and others may also want to have another group work on post-Dobbs personal privacy activity rights. That involves serious political issues way beyond my pay grade, and so I have no recommendations, aside from saying that The Sedona Conference® would be a good place to try and reach legal sanity. So too would my current personal favorite, the EDRM. Let’s all cooperate and try to figure this out together.

Pleading for further rules revisions is, however, within my limited wheel-house. Even without the further advice of scholars and experts, I am ready to commit to Professor Stuart’s admittedly reluctant suggestion that Rule 26(b)(1), Frankenstein or not, be revised once again, to include Privacy as a factor in proportionality analysis. You could get fancy with the revisions, but I am presently inclined to go with a short and simple solution and just include the words “the privacy considerations” on the 26(b)(1) list:

. . . and proportional to the needs of the case, considering the importance of the issues at stake in the action, the amount in controversy, the parties’ relative access to relevant information, the parties’ resources, the importance of the discovery in resolving the issues, the privacy considerations, and whether the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit.

When the Advisory Committee on Civil Rules takes up this proposal, and I urge them to begin the consideration process at their next meeting, they should not only consider individual, corporate and government privacy rights, but also the costs and burdens to litigants to protect these rights. That should be part of any Committee comments, which are always included with a rules revision and carry great weight.

Redaction can be very expensive. In my experience as a practitioner over the last couple of years, it is much more expensive and burdensome than privilege logs. More expensive still, is the effort to cull out irrelevant ESI for privacy protection in productions.

Good work has been accomplished in cutting the costs of privilege logs, but now we should focus on the related, but different issue of privacy protocols for other types of confidential information in civil discovery. (See eg. the work of the EDRM on privilege logs). Also see the excellent 2015, The Sedona Conference Commentary on the Protection of Privileged ESI. The Sedona publication discusses four general principles concerning privileged communications. The fourth principle is easily applicable to proportional privacy protection in civil discovery. It states “Parties and their counsel should make use of protocols, processes, tools, and technologies to reduce the costs and burdens associated with the identification, logging, and dispute resolution relating to the assertion of privilege.” The Sedona Conference Commentary on the Protection of Privileged ESI.

It is time to conclude and move beyond the privilege log projects and focus on related issues, other privacy protection concerns in discovery, including redaction protocols, court sealing protocols, filter team protocols, and confidentiality agreements and orders. We should look for ways to protect privacy rights, including the rule tweak here suggested. But in so doing we should be careful to control the costs. We do not want to create an accidental Frankenstein monster that eats up more time and money, not less. There are other many possibilities to both protect privacy and control costs. One might be expanding the scope of Evidence Rule 502 to include all types of confidential ESI within quick peek protection. Others solutions might be more technological in nature.

Another possible path with great promise is far greater use of Special Masters and discovery mediators. See: EDRM’s “Using Special Masters and Discovery Mediators to Resolve eDiscovery Disputes: A Bench Book for Judges and Attorneys 2022 Edition” (draft public comment version). Certainly there are initial upfront costs to use of a Special Master, but good ones can and will save far more expense to the parties than they cost. Far more. It will also speed things up. The costs of motion practice and excessive discovery remain an enormous cost and time waster, one that Masters and mediators with discovery and tech experience, knowledge are uniquely positioned to help control. This process can be abused too, as we are seeing now in the news.

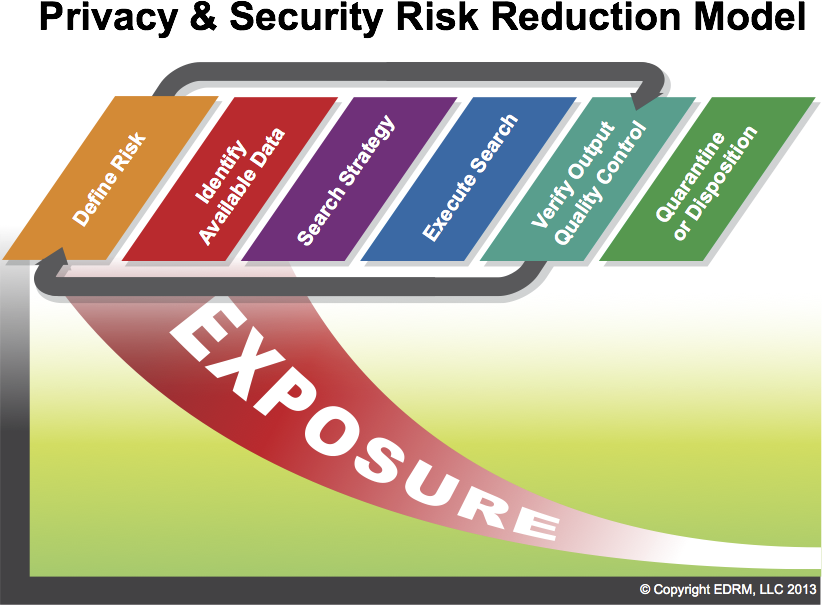

As usual, the success of any endeavor like this, of more rules, best practices and technology solutions, will depend on education of bench and bar, the cooperation of litigation counsel in implementation, and the active, learned supervision of judges. It will also depend heavily on pre-litigation records management and related record keeping best practices. See eg. the work of the EDRM going back to 2013 and the EDRM graphic here summarizing the protocol recommended.

Confidential, secret documents should not just be left lying around. And flushing secret materials down toilets is not proper, legal disposition. Companies, individuals and the government, especially the Executive branch of the federal government, must do a far better job. The laws governing confidential documents and privacy must be taken seriously and enforced. See eg. FULL TEXT OF THE OFFICIAL COURT REDACTED SEARCH WARRANT AGAINST DONALD TRUMP. The popular Internet meme that “privacy is dead” is a hacker myth, promoted by greedy tech-corporations, over-zealous journalists, foreign spies, criminals and kleptocrats everywhere. No society can function without privacy. A total lack of privacy is unnatural and wrong. It is an inalienable human right. The great Justice Brandeis correctly characterized “the right to be let alone” as “the right most valued by civilized men.” Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438 (1928) (dissent).

Privacy in discovery is a real problem in both civil and criminal litigation. See eg. In re Warrant, No. 22-8332-BER, 2022 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 150388 (S.D. Fla. Aug. 22, 2022). It requires our immediate attention, discussion and early response. Continued delay in addressing the discovery issues, the costs, benefits and burdens, will only make the situation worse. I come back to the proactive, stitch in time saying that I have analyzed before in the context of litigation. Professor Stuart’s article has started the stitching in a scholarly, but accessible manner. We should be grateful to her for that and continue the important work.

Ralph Losey Copyright 2022 – ALL RIGHTS RESERVED