A New Approach to Security in the WFH (home) and WFC (cloud) Era

In the Middle Ages, kings and other nobles secured their fiefdoms with a high-walled castle and a moat. The moat was designed to make it difficult for attackers to get close enough to the wall for ladders and grappling chains. The walls were meant to be impenetrable, or at least make it difficult for the barbarians at the gates to overcome. And, arrows and sometimes hot oil reigned down from the parapets to further dissuade those who made it through the first defenses.

The beauty of this security model is that a castle was almost impenetrable, protecting the lord’s treasures as well as the townspeople. It also forced the invader to lay siege, which was a difficult and time consuming way to wage war. The weakness of this approach was that once you breached the castle, your warriors could get just about anywhere. Even worse, your whole plan was at risk if an insider left a gate unlocked or a spy found the secret passage into the castle. For this form of security, insiders were the most dangerous threat.

Indeed, the famed “Trojan Horse” of ancient days was one method to breach these perimeter defenses. The large horse offered as a gift was filled with soldiers. Once the horse was brought into the castle, hidden soldiers could exit the rear and attack from inside the castle walls.

Castles Made of Sand?

As we moved forward into the 21st century, many followed this simple model for network security. Traditional castle-and-moat security networks focused on making it difficult to gain access from outside the network but assumed everyone was trustworthy inside by default. As in the Middle Ages, the problem with this approach was that once attackers gained access to the network, they could move about freely, harvesting corporate secrets or holding them for ransom. And, of course, many of the viruses and other malware created during this period functioned just like the Trojan horses of old, tricking insiders to carry them through the gates and wreaking havoc once they were inside.

Despite its known weaknesses, this security model was the standard during an era where most commuted into the office for work–and where the data stayed comfortably behind increasingly sophisticated firewalls. For those who had to work outside the walls, there were always the seemingly impenetrable (but often complicated) VPNs to provide a secure tunnel into the castle.

Then, of course, Covid hit. And to shake things up even more, it hit at exactly the time many companies were moving the crown jewels into the public cloud. Suddenly people were working from home (or their local coffee shop) and accessing data through cloud services rather than from behind corporate firewalls. What good are thick castle walls when the treasure is spread out all over the kingdom, along with the keys to the castle gates? And what to do with all that boiling oil?

Zero Trust: A New Security Paradigm

Over the past decade, network security professionals began to talk about a new security paradigm called “Zero Trust.” The term was originally coined by a Forrester Research analyst in 2010 but the concept had been explored by various defense agencies even before then. In 2018, Google announced that it had adopted Zero Trust networking after six years of hard work retrofitting their networks. By 2019, Gartner, a global research and advisory firm, listed Zero Trust security access as a core component of secure access service edge (SASE) solutions. And, perhaps most importantly, in May 2021, the Biden administration issued an executive order stating:

“Within 60 days of the date of this order, the head of each agency shall: . . . develop a plan to implement Zero Trust Architecture, which shall incorporate, as appropriate, the migration steps that the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) within the Department of Commerce has outlined in standards and guidance . . .”

Executive Order on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity

The order referred to and essentially adopted the Zero Trust principles set forth by the National Institute of Standards and Technology in their report on Zero Trust Architecture (NIST 800-207).

What is Zero Trust?

So what is Zero Trust? A Zero Trust security model is based on the principle that no one should be trusted whether they are inside or outside the network. In a Zero Trust world, verification should be required whenever someone seeks access to resources on the network. In effect, Zero Trust moves from President Regan’s “Trust but verify” to the more cynical: “Never Trust / Always Verify.”

The reasoning behind Zero Trust is that the traditional approach—trusting devices within the firewall, or within a VPN is not sufficient given todays advanced cyber threats and with the shift to this era of working from home (WFH) and working from the cloud (WFC). Zero Trust argues for mutual authentication and continuous verification of identities before granting access to systems and applications. User and device identity and integrity can be continuously verified without respect to location, and providing access to applications and services based on the confidence of device identity and device health in combination with user authentication.

Some call this perimeterless security to reflect the fact that perimeters are meaningless in a WFH and WFC environment. As data moved to the cloud, users began accessing work applications from different locations, at different times and from different devices. As Covid kicked in, closing down most offices, the situation simply got worse. Over the past few years, users had little choice but to work from home, accessing key information through the Internet and, increasingly, in the cloud. And most liked the freedom this new form of computing brought them.

NIST explains that Zero Trust is based on the following tenets.

- All data sources and computing services are considered resources.

- All communication is secured regardless of network location.

- Access to individual enterprise resources is granted on a per-session basis.

- Access to resources is determined by dynamic policy—including the observable state of client identity, application/service, and the requesting asset—and may include other behavioral and environmental attributes

- The enterprise monitors and measures the integrity and security posture of all owned and associated assets.

- All resource authentication and authorization are dynamic and strictly enforced before access is allowed.

- The enterprise collects as much information as possible about the current state of assets, network infrastructure and communications and uses it to improve its security posture.

While I won’t try to cover all of the tenets set forth by NIST, experts boil these principles down into three core principles:

1. Never Trust / Always Verify

The first step in any security model (and frankly even at the castle) is to make sure we know who is at the gate. Thus the user’s identity must be validated before we open the castle door. Certainly a username and password are important but many go beyond to seek another form of identification such as a randomly generated number sent out via a different medium, like a cell phone. In some circumstances, you can take authentication further by confirming factors such as location, device, or workload. All of this can be spoofed but each requirement makes it harder for the attacker.

More sophisticated implementations take this a step further. They architect the network environment in a way that clients–including internal ones–don’t have a direct path to any application or authentication service themselves. This can reduce the attack surface and thereby decrease the chance of the underlying system being compromised. Policies may be implemented to limit access based on time, location, address and other factors.

2. Least Privileged Access

One of the mantras in modern security is “Least Privilege.” And no, I am not talking about that kind of privilege. But yes I can say that if you waive the privilege, bad things can happen.

John Tredennick

One of the mantras in modern security is “Least Privilege.” And no, I am not talking about that kind of privilege. But yes I can say that if you waive the privilege, bad things can happen.

Least privilege is the idea that user access should be limited to what they need to do their job. In security circles, we might call it “need to know.” In the working world, we might call it “MYOB.”

In every case, there should be a policy setting forth what a user (or other “connecting entity”) is allowed to accomplish, what services can be accessed and, based on those and other requirements, whether or not, the access should be allowed based on current circumstances. Even if access is granted, it should be provisioned in a way that only allows the needed communication flows and nothing else.

3. Monitor and Reverify

Change is our only constant in this life. Because things can change, Zero Trust requires constant monitoring and continued verification. To remain secure, the system needs to verify rights and credentials each time a request is made. When circumstances change, that trusted user may turn into a threat. Or an impostor.

Ultimately, todays cyber security threat landscape demands that organizations adopt a posture where they assume that the network has been breached. Doing so will lead to a stronger security posture against potential threats, minimizing the impact if a breach does occur. As some have said: “Limit the blast radius.” In other words, limit the extent and reach of potential damage incurred by a breach by segmenting access to different parts of the network, applications and ultimately the data.

Don’t Forget the Basics: Of course, the basics still apply. Data should be encrypted in motion and at rest–regardless of whether your users are internal or external. Attacks from outside the network often start through phishing exploits that allow the attacker inside access.

Implementing a Zero Trust Network

Talking about Zero Trust and implementing it are two different things, but that shouldn’t keep you from getting started. Here are two key steps you can take to move toward a Zero Trust security environment.

1. Screen Resource Requests to Ensure Proper Access

At the heart of the Zero Trust is the notion that every request should be screened to make sure the requestor has access rights. With the castle and moat method, the emphasis was placed at the front gate. Once you got by the doorkeeper, you were pretty much on your own.

Zero Trust recognizes that rights can change, even in the middle of a session, and thus access privileges should be confirmed with each request. Thus, if a malicious pattern is spotted, the system can quickly shut down access limiting the harm done.

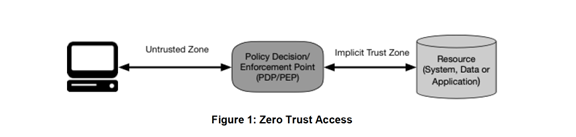

NIST recommends placing a “Policy Server” between the requestor and the desired resource.

As shown in the diagram, the policy servers job is to ensure that the subject is authentic and the request is valid. If it is valid, the policy server will pass over the credentials to the resource allowing it to honor the request.

2. Limit Access to Resources through Authorization Tickets

Many systems allow the user direct access to documents on the associated file server. This can be a security risk because a user may attempt to access other documents through nefarious means such as SQL injection scripts or even smart URL guesswork. The links can also be passed to outside individuals, although in most cases they still have to get inside the castle walls to view or download the files.

In a Zero Trust environment, document requests should first pass through a separate Authorization Server. The server’s job is two-fold, consistent with the Zero Trust principles above. First, the server checks to determine whether the user has the right to access the requested document. If that test is met, the server then creates a token which is sent to the storage device to carry out the request.

The key here is that the token is both encrypted and time-limited. The authorized user can access the document during a short window before the token expires. If the link is passed to another, potentially unauthorized individual, they will likely find that it has expired.

Conclusion

Zero Trust is a relatively new concept but it is catching on fast for private and public networks. According to CNBC, a large percentage of corporations are moving from VPNs in favor of Zero Trust, stating that the trend began during the pandemic, when organizations replaced their virtual private network (VPN) access with zero trust network access (ZTNA).

“We talked with 43 organizations using ZTNA, and of those 26 said they had migrated away from VPN toward zero trust for better performance.”

Government agencies have similarly been directed to move to Zero Trust by 2024, a deadline which they may or may not meet. Amazon (AWS) and Microsoft have joined Google in adopting Zero Trust models for their infrastructure services as well.

That said, it should be noted that Zero Trust is more of a concept that a packaged security system. As one expert who was developing Zero Trust architectures before they had a name noted:

“One of the common mistakes we see enterprises IT leaders and many cybersecurity experts make is to think of Zero Trust as a product. it is not. Zero Trust is a concept where an organization has Zero Trust in a specific individual, supplier or technology that is the source of their cyber risk. One needs to have Zero Trust in something and then act to neutralize that risk. Thus buying a Zero Trust product makes no sense unless it is deployed as a countermeasure to specific cyber risk. Buying products should be the last step taken not the first.”

From Zero Trust Will Yield Zero Results without a Risk Analysis by Junaid Islam

In the final analysis, “secure” means that no one can be trusted by default from inside or outside the network, and verification should be required from everyone and everything trying to gain access to resources on the network. This extra layer of security can help prevent data breaches and even reduce the threat of ransomware. As one respected group reported, “Studies have shown that the average cost of a single data breach is over $3 million.”

Zero Trust? As some might say: “Zero Trust is better than no Trust at all.”

Author’s Acknowledgement:

I wish to thank Daniel Cybulski and Bob Flores, both Merlin Advisory Board members with extensive credentials in cyber security defenses, for their guidance and help with this article. Both had long careers with the CIA before moving to the private sector to help governments, companies and other institutions fight cyber crime.