[EDRM Editor’s Note: The opinions and positions are those of Michael Berman.]

One role of an attorney handling ESI is to function as a translator between computer scientists and forensic experts, on the one hand, and laypersons, such as clients and Judges, on the other.

In Boulder Falcon, the producing party provided load files, but did not inform the recipient. That triggered a discovery battle. Anyone with technological competence should be able to recognize a load file and “notice” should not be necessary.

Michael Berman.

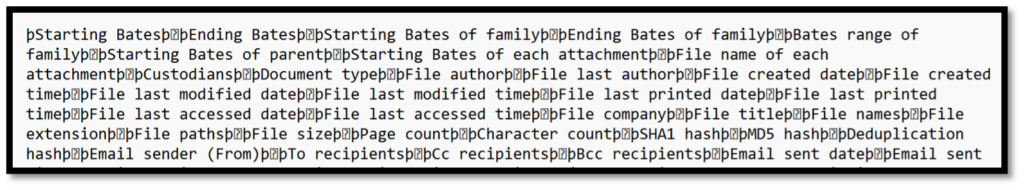

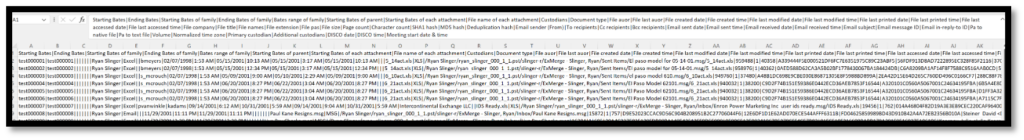

When you look at a “load file” it can be intimidating. Here is the .dat part of a load file created from DISCO, a litigation review platform, using Enron data. It was opened in Notepad:

To improve legibility, although not readability, I have increased the font of the first few rows:

What is a “load file”? The Sedona Conference defines it as:

Load File: A file that relates to a set of scanned images or electronically processed files, and that indicates where individual pages or files belong together as documents, to include attachments, and where each document begins and ends. A load file may also contain data relevant to the individual documents, such as selected metadata, coded data, and extracted text. Load files should be obtained and provided in prearranged or standardized formats to ensure transfer of accurate and usable images and data.

Sedona Conference Glossary, Fifth Edition.pdf (thesedonaconference.org), 21 Sedona Conf. . 263 (2020).

Why is a “load file” important in certain productions?

A “load file” is actually several files that work together to “load and organize information within e-discovery software so that the documents may be viewed, searched[,] and filtered.” Each “load file” contains a raw image of each document and other files containing metadata associated with each raw image. When all the files in a load file are uploaded into discovery review software, the load file “ties all the information together within the software by connecting the image files to the right text and metadata files.” Thus, a full load file makes the raw image come “alive” by making all links in an email attachment become easily accessible with a mouse click just as they would be if they were being viewed on the email recipient’s computer. Thus, in the language of Rule 34, load files allow a party to produce electronically stored information “in a form … in which it is ordinarily maintained.”

However, if discovery review software is not used to unlock the power of these load files, then the reviewer of the data is left with a bunch of seemingly extraneous files and raw images of the documents. The raw images of the scanned documents contain no metadata, which means that what you see is what you get. In other words, all links to email attachments are not active, and the attachments to each email may not directly follow their parent email in the production. This means that an email and its attachment may be several hundred pages apart in the production. To understate the point, making sense of the documents becomes extremely difficult.

Boulder Falcon, LLC v. Brown, 2023 WL 2662187, at *2 (D. Utah Mar. 28, 2023)(cleaned up)(citing The Sedona Conference).[1]

A mere human being can easily transform an indecipherable load file into a human-readable document.

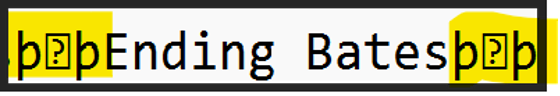

This DISCO load file uses two separators:

Other programs may use different characters as separators; however, the concepts are unchanged.

Here is a way of making a load file readable to carbon life forms.

First, in Notepad, search and replace the “field delimiter” – the square with an internal question mark – with a Pipe character – – |

Next, and again in Notepad, search and replace the “quote” character – the funny looking “P” – with nothing.

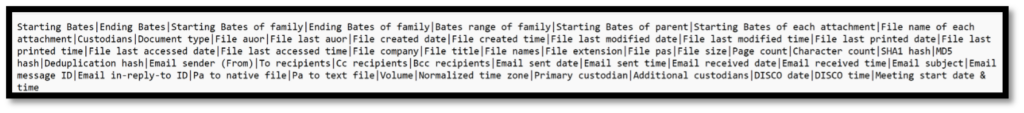

This is the result – still unreadable by a human:

Next, copy (Ctrl-A, then Ctrl-C) and paste (Ctrl-V) the results into Excel.

This is the result – still unreadable by a human:

In Excel, navigate to the “Data” tab and then “Text to Columns.”

Next, choose the radio button option of “Delimited – Characters such as commas or tabs separate each field.”

Then click “Next.”

On the following screen, under “Delimiters,” click on “Other” and insert the Pipe character – – |.

Click “Next.” Leave the “Column data format” with the default radio button of “General.” The “Data preview” screen will predict your output.

Click “Finish.”

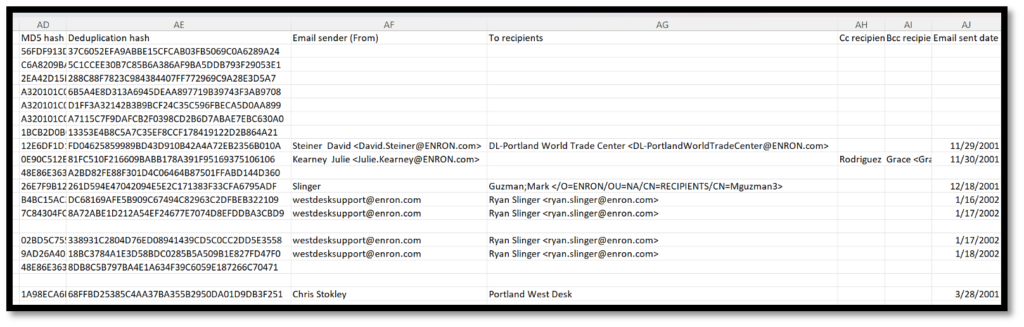

Voilà! The result will be a load file that we can easily read:

Because the fonts are small on this blog, I have expanded below part of the load file:

[1] In Boulder Falcon, the producing party provided load files, but did not inform the recipient. That triggered a discovery battle. Anyone with technological competence should be able to recognize a load file and “notice” should not be necessary.