[Editor’s Note: EDRM is proud to publish Ralph Losey’s advocacy and analysis. The opinions and positions are Ralph Losey’s copyrighted work.]

On April 19, 2024, the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules for federal courts faced a critical question: Does AI-generated evidence, including deepfakes, demand new rules? The Committee’s surprising answer—’not yet.’ Was that the right call? Will they change their mind when they meet in November again right after the elections?

Part One analyzes the various rule change proposals. Chief among them is the proposal by Judge Paul Grimm (retired) and Professor Maura Grossman, who are well known to all legal tech readers. Several other interesting proposals were considered and discussed. You will hear the nerds inside view of the key driving facts at play here, the danger of deepfakes, the power of audio-video evidence, jury prejudice and the Liar’s Dividend. Part One also talks about why the Evidence Rules Committee chose not to act and why you should care.

Part Two will complete the story and look at what comes next with the meeting of November 8, 2024. It will also include a discussion of the latest article by Paul Grimm, Maura Grossman and six other experts: Deepfakes in Court: How Judges Can Proactively Manage Alleged AI-Generated Material in National Security Cases. They are all trying, once again, to push the Committee into action. Let us hope they succeed.

Summary of the Evidence Committee’s Decision and the Leadership of its Official Reporter

The Committee, under the strong leadership of its official Reporter for the last twenty-eight years, Daniel J. Capra, considered multiple proposals to amend the Rules of Evidence, but rejected them all. Professor Capra cited the need for further development. For now, courts must manage the significant new challenges of AI with existing rules.

The key segment of the Committee’s work is the 26-page memorandum found at Tab 1-A of the 358-page agenda book. It was written by Professor Daniel J. Capra, Fordham University School of Law and Adjunct Professor at Columbia Law. Dan Capra is a man almost my age, very powerful and respected in academic and judicial circles. He is a true legend in the fields of evidence, legal ethics and education, but he is no nerd. His comments and the transcript of his interaction with two of the top tech-nerds in law, Judge Paul Grimm (retired) and Professor Maura Grossman, make clear that Professor Capra lacks hands-on experience and deep understanding of generative AI.

That is a handicap to his leadership of the committee on the AI issues. His knowledge is theoretical only, and just one of many, many topics that he reads about. He does not teach AI and the law, as both Grimm and Grossman do. This may explain why he wanted to just wait things out, again. He recommended, and the committee agreed, apparently with no dissenters, to reject the concerns of almost all of the hands-on nerds, including all of the legal experts proposing rule changes. They all warn of the dangers of generative AI and deepfakes to interfere with our evidence based system of justice. It may even make it impossible to protect our upcoming election from deepfake interference. Daniel Capra gives consideration to some danger, but thinks the concerns are overblown and the committee should continue to study and defer any action.

Pop Art style image by Ralph Losey using his Visual Muse GPT.

Evaluation of the Pending Danger of Deepfakes

For authority that the dangers of deepfake are overblown, and so no rule changes are necessary, Professor Capra cites two articles. Professor Capra’s Memorandum to the Committee at pgs. 25-26 (pgs. 38-39 of 358). The first is not persuasive, to say the least, a 2019 article in the Verge, Deepfake Propaganda is not a Real Problem, THE VERGE (Mar. 15, 2019). The article was written by Russell Brandom, who claims expertise on “the web, the culture, the law, the movies, and whatever else seems interesting.”

The second article was better, Riana Pfefferkorn, Deepfakes in the Courtroom, 29 Public Interest Law Journal 245, 259 (2020). Still, it was written in 2020 and so now is way out of date. My research discovered that Riana Pfefferkorn has published a much more recent paper pertaining to deepfakes, Addressing Computer-Generated Child Sex Abuse Imagery: Legal Framework and Policy Implications (Lawfare, February 2024). In the Introduction at page-2 of this well written paper she says:

Given the current pace of technological advancement in the field of generative ML, it will soon become significantly easier to generate images that are indistinguishable from actual photographic images depicting the sexual abuse of real children.

Addressing Computer-Generated Child Sex Abuse Imagery: Legal Framework and Policy Implications (Lawfare, February 2024).

For Ms. Pfefferkorn the problem of deepfakes is now a very real and urgent problem. At page 25 of the paper she asserts: “There is an urgent need, exacerbated by the breakneck pace of advancements in machine learning, for Congress to invest in solving this technical challenge.”

Professor Capra and the committee see no “urgent need” to act. They do so in part because of their belief that new technology will emerge (or already exists) that is able to detect deepfakes and so this problem will just go away. Professor Capra has one expert to support that view, Grant Fredericks, the president of Forensic Video Solutions. I looked at the company website and see no claims to development or use of any new technologies. Capra relies on the vendor promises to detect fake videos and keep them out of evidence, “both because they can be discovered using the advanced tools of his (Fredricks) trade and because the video’s proponent would be unable to answer basic questions to authenticate it (who created the video, when, and with what technology.” Professor Capra’s Memorandum to the Committee at pg. 26 (pg. 39 of 358).

Capra’s memorandum to the Committee at first discusses why GenAI fraud detection is so difficult. He explains the cat and mouse competition between image generation software makers and fraud detection software companies. Oddly enough, his explanation seems correct to me, and so appears to impeach his later conclusion and the opinion of his expert, Fredericks. Here is the part of Capra’s memorandum that I agree with:

Generally speaking, there is an arms race between deepfake technology and the technology that can be employed to detect deepfakes. . . any time new software is developed to detect fakes, deepfake creators can use that to their advantage in their discriminator models. A New York Times report reviewed some of the currently available programs that try to detect deepfakes. The programs varied in their accuracy. None were accurate 100 percent of the time.

Memorandum to the Committee at pg. 17 (pg. 30 of 358).

Professor Capra supports his statement that “none were accurate 100 percent of the time,” by citing to a NYT article, Another Side of the A.I. Boom: Detecting What A.I. Makes (NYT, May 19, 2023). I read the article and it states that there are now more than a dozen companies offering tools to identify whether something was made with artificial intelligence, including Sensity AI, Optic, Reality Defender and FakeCatcher. The article repeats Professor Capra’s arms race scenario, but adds how the detector software always lags behind. That is common in cybersecurity too, where the defender is always at a disadvantage. Here is a quote from the NYT article:

Detection tools inherently lag behind the generative technology they are trying to detect. By the time a defense system is able to recognize the work of a new chatbot or image generator, like Google Bard or Midjourney, developers are already coming up with a new iteration that can evade that defense. The situation has been described as an arms race or a virus-antivirus relationship where one begets the other, over and over.

Another Side of the A.I. Boom: Detecting What A.I. Makes (NYT, May 19, 2023).

That has always been my understanding too, which is why I cannot believe that new technology is around the corner to finally make detection foolproof or that Grant Fredericks has a magic potion. I think it is more likely that the spy versus spy race will continue and uncertainty will be with us for a long time. Still, I sincerely hope that Professor Capra is right, and the fake image dangers are overstated. That’s my hope, but reason and science tells me that’s a risky assumption and we should mitigate our risks by making some modest revisions to the rules now. I would start with the two short proposals of Grimm and Grossman.

50s Pop Art style image by Ralph Losey using his Visual Muse GPT.

Professor Capra’s Discussion of the Proposed Rule Amendments

There were four rule change proposals before the committee in 2024. One by Professor Andrea Roth of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, a second by Professor Rebecca Delfino of Loyola Law School and a third by Judge Paul Grimm (retired) and Professor Maura Grossman, already well known to most of my readers. I omit discussion here of a fourth proposal by John LaMonaga. in the interests of time, but you can learn about it in Professor Capra’s Memorandum to the Committee at pgs. 23-25 (pgs. 36-38 of 358). Also see John P. LaMonaga, A Break from Reality: Modernizing Authentication Standards for Digital Video Evidence in the Era of Deepfakes, 69 Am. U.L. Rev. 1945, 1984 (2020).

Professor Andrea Roth’s Rule Proposals

Professor Roth’s suggestions are nerdy interesting and forward thinking. Her suggestions are found in Professor Capra’s Memorandum to the Committee at pgs. 10-13 (pgs. 23-26 of 358) and Capra’s critical comments of the proposals follow at pgs. 13-16 (pgs. 26-29 of 358). I urge interested readers to check out her proposals for yourself. Capra’s comments seem a bit overly critical and I look forward to hearing more from her in the future.

Here is a comment from Capra to one of her proposals, to add a new, independent subdivision to Rule 702. Testimony by Expert Witnesses.

The proposal addresses what could be thought to be a gap in the rules. Expert witnesses must satisfy reliability requirements for their opinions, but it is a stretch, to say the least, to call machine learning output an “opinion of an expert witness.”

Memorandum to the Committee at pg. 11 (pg. 24 of 358).

Oh really? A stretch, to say the least. Obviously Capra is not familiar with my work, and that of many others in AI, on the use of generative AI personas as experts. See e.g. Panel of AI Experts for Lawyers; and, Panel of Experts for Everyone About Anything. Also see: Du, Li, Torralba, Tenenbaum and Mordatch, Improving Factuality and Reasoning in Language Models through Multiagent Debate, (5/23/23).

Image by Ralph Losey (who consults with them frequently) using his Visual Muse GPT.

For me Andrea Roth’ proposals are not a stretch, to say the least, but common sense based on my everyday use of generative AI.

Andrea Roth also suggests that Rule 806. Attacking and Supporting the Declarant’s Credibility be amended to allow opponents to “impeach” machine output in the same way as they would impeach hearsay testimony from a human witness. Professor Capra criticizes that too, but this time is more kind, saying at page 13 of his memo.

The goal here is to treat machine learning — which is thinking like a human — the same way that a human declarant may be treated. Thought must be given to whether all the forms of impeachment are properly applicable to machine learning. . . The question is whether an improper signal is given by applying 806 wholesale to machine related evidence, when in fact not all the forms of impeachment are workable as applied to machines. That said, assuming that some AI-related rule is necessary, it seems like a good idea, eventually, to have a rule addressing the permitted forms of impeachment of machine learning evidence.

Memorandum to the Committee at pg. 13.

I thought Andrea Roth’s suggestion was a good one. I routinely cross examine AI on their outputs and opinions. It is an essential prompt engineering skill to make sure their opinions are reliable and understand the sources of their opinions.

Due to concerns over the length of this article I must defer further discussion of Professor Andrea Roth’s work and proposals for another day.

Impressionism style image by Ralph Losey using his Visual Muse GPT.

Professor Rebecca Delfino’s Proposal to Remove Juries From Deepfake Authenticity Findings

Professor Rebecca Delfino of Loyola Law School is a member of the committee’s expert panel. She is very concerned about the dangers of the powerful emotional impact of audiovisuals on jurors and the costs involved in authenticity determinations. Her recent writings on these issues include: Deepfakes on Trial: A Call to Expand the Trial Judge’s Gatekeeping Role To Protect Legal Proceedings from Technological Fakery, 74 HASTINGS L.J. 293 (2023); The Deepfake Defense—Exploring the Limits of the Law and Ethical Norms in Protecting Legal Proceedings from Lying Lawyers, Loyola Law School, 84 Ohio St. L.J., Issue 5 1068 [2024]; Pay-To-Play: Access To Justice In The Era Of Ai And Deepfakes, 55 Seton Hall L.Rev., Book 3, __ (forthcoming 2025) (Abstract: “The introduction of deepfake and AI evidence in legal proceedings will trigger a failure of the adversarial system because the law currently offers no effective solution to secure access to justice to pay for this evidence for those who lack resources.“) Professor Rebecca Delfino argues that the danger of deepfakes demands that the judge decide authenticity, not the jury.

Sub-Issue on Jury Determinations and the Psychological Impact of Deepfakes

I am inclined to agree with Professor Delfino. The important oral presentation of Paul Grimm and Maura Grossman to the committee shows that they do too. We have a transcript of that by Fordham Law Review, Daniel J. Capra, Deepfakes Reach the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules, 92 Fordham L.R. 2491 (2024) at pgs. 2421-2437.

Paul and Maura make a formidable team of presenters, including several notable moments where Maura shows Capra and his committee a few deepfakes she made. In the first she put Paul Grimm’s head on Dan Capra’s body, and vica versa, which caused Dan to quip “I think you lose in that trade, Paul.” Then she asked the panel to close their eyes and listen to what turned out to be a fake audio of President Biden directing the Treasury Depart to make payment of $10,000 to Daniel Capra. Id. at pgs. 2427-2427.

I thought this was great ploy. Maura then told the committee she made it in seconds using free software on the internet and that with more work it would sound exactly like the President. Id. at 2426-2427. Professor Capra, who has been stung before by surprise audio, did not seem amused and his ultimate negative recommendations show he was not persuaded.

Here are excerpts of the transcript of the next section of their presentation to the committee.

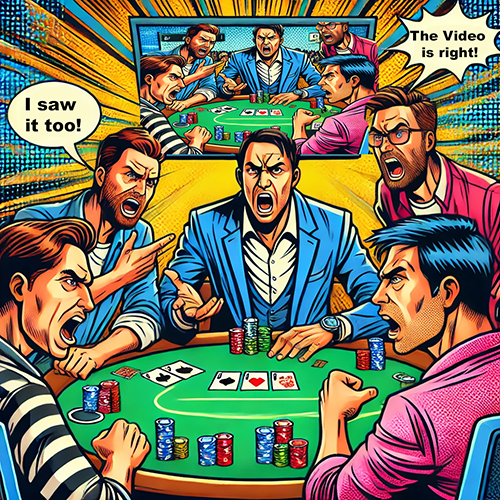

PROF. GROSSMAN. Because there are two problems that these deepfakes and that generative AI cause. One is we’re moving into a world where none of us are going to be able to tell what is real from not real evidence—which of these videos are real, which of these aren’t. And I’m very worried about the cynicism and the attitude that people are going to have if they can’t trust a single thing anymore because I can’t use any of my senses to tell reality.

And the other is what they call the liar’s dividend, is why not doubt everything, even if it’s in fact real, because now I can say, “How do you know it’s not a deepfake?”, and we saw a lot of that in the January 6 cases. Some of the defendants said, “That wasn’t me there” or “How do you know it was me?”187 Elon Musk used that defense already.188 So you’re going to have both problems: one where it really is fake, and now every case going to require an expert; and the other where it really is real evidence, and you don’t want to become so cynical that you don’t believe any of it.

Deepfakes Reach the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules, supra at pgs. 2427-2428.

To quote an NPR article on the “Liar’s Dividend:”

When we entered this age of deepfakes, anybody can deny reality. … That is the classic liar’s dividend.

The liar’s dividend is a term coined by law professors Bobby Chesney and Danielle Citron in a 2018 paper laying out the challenges deepfakes present to privacy, democracy, and national security. The idea is, as people become more aware of how easy it is to fake audio and video, bad actors can weaponize that skepticism. “Put simply: a skeptical public will be primed to doubt the authenticity of real audio and video evidence,” Chesney and Citron wrote.

Shannon Bond, People are trying to claim real videos are deepfakes. The courts are not amused (NPR, 5/8/23).

Surrealistic-style image by Ralph Losey using his Visual Muse GPT.

Back to the transcript of the presentation of Grossman and Grimm to the committee: Judge Grimm went on to explain why, under the current rules, the jury may often have to make the final determination of authenticity. They emphasize that even if the jury decides it is inauthentic, the jury will still be tainted by the process, as they cannot unsee what they have seen. Instructions from a judge to disregard the video seen will be ineffective.

JUDGE GRIMM: Now there’s one monkey wrench in the machinery: When you’re dealing with authentication, you’re dealing with conditional relevance if there’s a challenge to whether or not the evidence is authentic. And so, if you’re going to have a factual situation where one side comes in and says, “This is the voice recording on my voicemail, this is the threatening message that was left on my voicemail, that’s Bill, I’ve known Bill for 10 years, I am familiar with Bill’s voice, that is plausible evidence from which a reasonable factfinder could find that it was Bill.”

If Bill comes in and says, “That was left at 12:02 PM last Saturday, at 12:02 PM I have five witnesses who will testify that I was at some other place doing something else where I couldn’t possibly have left that,” that is plausible evidence that it was not Bill.

And when that occurs, the judge doesn’t make the final determination under Rule 104(a).209 The jury does.210 And that’s a concern because the jury gets both versions now. It gets the plausible version that it is; it gets the plausible version that it’s not. The jury has to resolve that factual dispute before they know whether they can listen to that voicemail and take it into consideration as Bill’s voice in determining the outcome of the case.

PROF. GROSSMAN: Can I add just one thing? Two studies you should know about. One is jurors are 650 percent more likely to believe evidence if it’s audiovisual, so if that comes in and they see it or hear it, they are way more likely to believe it.211 (Rebecca A. Delfina, Deepfakes on Trial: A Call to Expand the Trial Judge’s Gatekeeping Role to Protect Legal Proceedings from Technological Fakery, 74 HASTINGS L.J. 293, 311 fn.101–02 (2023)).And number two, there are studies that show that a group of you could play a card game. I could show you a video of the card game, and in my video it would be a deepfake, and I would have one of you cheating. Half of you would be willing to swear to an affidavit that you actually saw the cheating even though you didn’t because that video—that audio/video, the deepfake stuff—is so powerful as evidence that it almost changes perception.212 (See Wade, Green & Nash, Can Fabricated Evidence Induce False Eyewitness Testimony?, 24 APPLIED COGNITIVE PSYCH. 899 (2010)).

Pop Art style image by Ralph Losey using his Visual Muse GPT.

CHAIR SCHILTZ: But why would judges be any more resistant to the power of this than jurors?

JUDGE GRIMM: Well, for the same reason that that we believe that in a bench trial that the judge is going to be able to distinguish between the admissible versus the non-admissible.CHAIR SCHILTZ: I know, but it is often fictional, right? There are certain things that I really am no better at than a juror is, like telling a real picture from an unreal picture, or deciding which of these two witnesses to believe—between the witness who says, “That’s his voice,” and the witness who said, “It couldn’t have been me.” Why am I any better at that than a juror?

Deepfakes Reach the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules, supra at pgs. 2427-2428.

JUDGE GRIMM: You might be better than a juror because you, as the judicial officer, can have it set up so that you have a hearing beforehand, which is a hearing on admissibility that the jury is not going to hear; and you have the witnesses come in, and you hear them; or you have a certificate under Rule 902(13). Also, you will be a repeat player.

PROF. GROSSMAN: Right. And you would at least know the questions to ask: How was this algorithm trained? Was it tested? What was it tested on? Who did the testing? Were they arm’s length? What’s the error rate?

JUDGE GRIMM: And order the discovery that the other side can have to be able to have the opportunity to challenge it by bringing that in.

CHAIR SCHILTZ: Yes, I get that part.

The Chair, Hon. Patrick J. Schiltz asks good questions here and understands the issue. Anyone should be far more comfortable having a judge, especially one like Judge Schiltz, making the hard calls instead of a room of randomly called jurors. There is no question in my mind that judges are far better qualified than jurors to make these determinations. All three experts were making that point, Paul Grimm, Maura Grossman and Rebecca Delfino.

Post-apocalyptic-futurism style image by Ralph Losey using his Visual Muse GPT.

Back to Professor Rebecca Delfino’s Proposal

Here is Professor Capra explanation to the committee of how Professor Delfino’s proposed rule changes would work. Unfortunately, I have not found any argument from her on her proposal, just Capra’s explanation and he ultimately rejected it.

Professor Rebecca Delfino argues that the danger of deepfakes demands that the judge decide authenticity, not the jury.19 She contends that “[c]ountering juror skepticism and doubt over the authenticity of audiovisual images in the era of fake news and deepfakes calls for reallocating the fact finding authority to determine the authenticity of audiovisual evidence.” She contends that jurors cannot be trusted to fairly analyze whether a video is a deepfake, because deepfakes appear to be genuine, and “seeing is believing.” Professor Delfino suggests that Rule 901 should be amended to add a new subdivision (c), which would provide:

Memorandum to the Committee.

901(c). Notwithstanding subdivision (a), to satisfy the requirement of authenticating or identifying an item of audiovisual evidence, the proponent must produce evidence that the item is what the proponent claims it is in accordance with subdivision (b). The court must decide any question about whether the evidence is admissible.

She explains that the new Rule 901(c) “would relocate the authenticity of digital audiovisual evidence from Rule 104(b) to the category of relevancy in Rule 104(a)” and would “expand the gatekeeping function of the court by assigning the responsibility of deciding authenticity issues solely to the judge.”

The proposed rule would operate as follows: After the pretrial hearing to determine the authenticity of the evidence, if the court finds that the item is more likely than not authentic, the court admits the evidence. The court would instruct the jury that it must accept as authentic the evidence that the court has determined is genuine. The court would also instruct the jury not to doubt the authenticity, simply because of the existence of deepfakes. This new rule would take the Memorandum to the Committee at pgs. 22-23 (pgs. 35-36 of 358).

This proposal sounds feasible to me. It could help reduce the costs of expert battles and counter the Liar’s Dividend and CSI Effect. Professor Capra made a few helpful comments as to how Professor Delfino’s language would benefit by a few minor changes. But those are moot points because he respectfully declined to endorse the proposal noting that: “Given the presence of deepfakes in society, it may well be that jurors will do their own assessment, regardless of the instruction.” He seems to miss the point of minimizing the psychological impact on jurors by keeping deepfake videos and audios out of the jury room.

Photorealistic style by Ralph Losey using his Visual Muse GPT.

Paul Grimm and Maura Grossman’s Two Rule Proposals

Two rule change proposals were made by Paul Grimm and Maura Grossman. Paul and Maura are both well known to my readers as progressive leaders in law and technology. They have been working on these evidentiary issues for years. See e.g., The GPTJudge: Justice in a Generative AI World, 23 Duke Law & Technology Review 1-34 (2023).

They were invited to present their proposals to the Committee to modify Rule 901(b)(9) for AI evidence and add a new Rule 901(c) for “Deepfake Evidence.” The transcript of their presentation was referred to previously. Deepfakes Reach the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules, 92 Fordham L.R. 2491 (2024) at pgs. 2421-2437. I recommend you read this in full.

Here are the two rule changes Paul and Maura proposed:

901 Examples. The following are examples only—not a complete list—of evidence that satisfies the requirement [of Rule 901(b)]:

Deepfakes Reach the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules, 92 Fordham L.R. 2491 (2024) at pgs. 2421-2437.

(9) Evidence about a Process or System. For an item generated by a process or system:

(A) evidence describing it and showing that it producesan accuratea valid and reliable result; and

(B) if the proponent concedes that the item was generated by artificial intelligence, additional evidence that:

(i) describes the software or program that was used; and

(ii) shows that it produced valid and reliable results in this instance.

Proposed New Rule 901(c) to address “Deepfakes”:

901(c): Potentially Fabricated or Altered Electronic Evidence. If a party challenging the authenticity of computer-generated or other electronic evidence demonstrates to the court that it is more likely than not either fabricated, or altered in whole or in part, the evidence is admissible only if the proponent demonstrates that its probative value outweighs its prejudicial effect on the party challenging the evidence.

Deepfakes Reach the Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules, 92 Fordham L.R. 2491 (2024) at pgs. 2421-2437.

As you can see their proposed new rule 901(c) largely takes the jury out of the “fake or real” determination and in so doing takes away most of the potential prejudicial impact upon jurors. The burden of possible unconscious prejudice and emotional impact from viewing inadmissible deepfake media would be born solely by the judge. As discussed, the judge is better trained for that and will have the benefit of pretrial hearings and expert testimony. The jury retains its traditional power over all other determinations of justiciable facts. Note that this proposal does not go as far as Professor Delfino’s in taking determinations away from the jury and expanding the gatekeeper role of the judge. More on 901(c) in general will follow, but first the proposed revisions to Rule 901(b)(9).

Accuracy v. Reliability and Validity

Professor Capra killed both of the Grimm and Grossman proposals after asking for input from only one expert on his panel, the one who happened to be the only one on the panel proposing a competing rule change, Professor Rebecca Wexler. You might expect her to oppose Grimm and Grossman’s proposal, lobbying instead for her own rival proposals. To her credit she did not. Instead, in Capra’s own words, she “supported the proposals but suggested that they should be extended beyond AI. Memorandum to the Committee at pgs. 9-10 (22-23 of 358). As to the amendment to Rule 901(b)(9) Professor Wexler said:

Re: the first Grimm/Grossman proposal, it may well be that the standard for authenticating system/process evidence should require a showing that the system/process produces “valid” and “reliable” results, rather than merely accurate results. . .

I can understand the push to add a reliability requirement to 901(b)(9). It’s true that ML systems could rely on an opaque logic that gives accurate results most of the time but then sometimes goes off the rails and creates some seemingly illogical output. But manually coded systems can do the same thing. They could be deliberately or mistakenly programmed to fail in unexpected conditions, or even once every hundred runs on the same input data. So if reliability is important, why not make it a broader requirement?

Memorandum to the Committee at pg. 9 (22 of 358).

Still, Capra seemed to give little weight to her input and stuck with his objection. He continued to insist that the use of the words “valid and reliable” instead of “accurate” in Rule 901(b)(9) is an unnecessary and confusing complication. It appears that he does not fully understand the nerdy AI based technical reasons behind this change. Notice that Capra once again relies on a vendor, Evidently AI, to try to support his attempt to get technical. Professor Capra says in his Memorandum to the Committee at page 7 (20 of 358).

The proposal (on Rule 901(b)(9)) distinguishes the terms “validity,” “reliability,” and “accuracy.” That is complicated and perhaps may be unnecessary for a rule of evidence. . . As to “accuracy,” the proposal rejects the term, but in fact there is a good deal of material on machine learning that emphasizes “accuracy.” See, e.g., https://www.evidentlyai.com/classification-metrics/accuracy-precision-recall. . . The whole area is complicated enough without adding distinctions that may not make a difference.

Memorandum to the Committee at pg. 7 (20 of 358).

Too complicated, really? Meaningless distinctions? Maura Grossman and Paul Grimm, who have extensive experience actually using these evidence rules in court, and are both bonafide nerds (especially Maura), were not, to my knowledge, given an opportunity to respond to these criticisms. I have not talked to them about this but would imagine they were not pleased.

Image by Ralph Losey using his Visual Muse GPT.

To be continued. . . Part Two of this article will complete the analysis of the Grimm – Grossman rule proposals and look at what comes next with the Rule Committee meeting of November 8, 2024. It will also include discussion of the latest article by Judge Paul Grimm (retired), Professor Maura Grossman and six other experts: Deepfakes in Court: How Judges Can Proactively Manage Alleged AI-Generated Material in National Security Cases. They are all trying, once again, to push the Committee into action. Let us hope they succeed. Don’t look up, but an election is coming.

Dark fantasy style image by Ralph Losey using his Visual Muse GPT.

Ralph Losey Copyright 2024 – All Rights Reserved

Assisted by GAI and LLM Technologies per EDRM GAI and LLM Policy.