[EDRM Editor’s Note: EDRM is proud to publish Ralph Losey’s advocacy and analysis. The opinions and positions are Ralph Losey’s copyrighted work. All images in this article were created by Ralph Losey using AI. This article is published here with permission.]

The rise of legal AI has sparked a familiar fear: that our hard-won expertise might be absorbed into machines. That lawyers will be off-loaded—our reasoning encoded, commodified, and reduced to prompts. That we’ll be sidelined into “hand-holding” roles—providing comfort more than cognition, reassurance instead of reasoning. Or worse, that we’ll be replaced altogether.

These anxieties are understandable. But they rest on a flawed premise: that all legal judgment can be captured, transferred, and automated. I’ve long disagreed. This article lays out why and how AI, when properly harnessed, can amplify human lawyers rather than erase them.

One recent LinkedIn post by Damien Riehl distilled this anxiety into what he called “the trillion-dollar question;” how firms capture—and try to monetize—lawyerly know-how. His reflection was a catalyst for this piece. But the ideas here reflect a position I’ve long held: AI can assist, but it cannot replicate the highest levels of legal reasoning. The future of the profession depends on knowing the difference and building systems that keep humans in the lead.

Introduction

The foundational fear behind AI replacement anxiety is based on a flawed assumption: that all of a lawyer’s judgment can be taught to a machine. Some of it can, no question. But the most valuable parts—the creative, emergent, contextual decisions—cannot. Legal expertise isn’t just about rules. It’s about timing, presence, and insight.

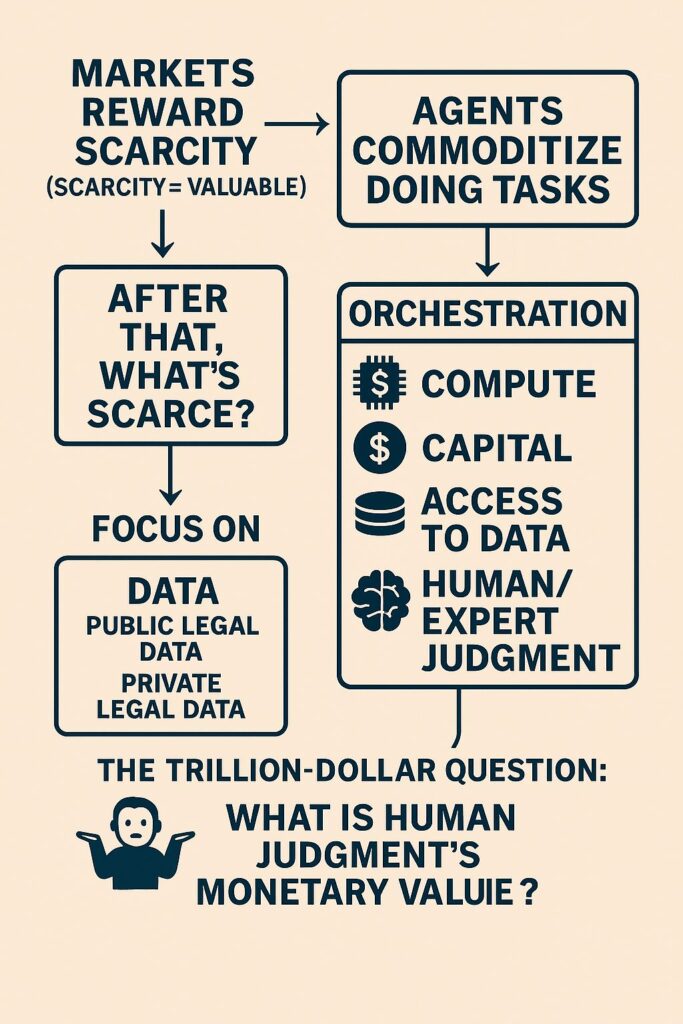

Damien Riehl recently posted on LinkedIn what he calls “the trillion-dollar question,” asking how firms value—and try to bottle—lawyerly know-how. His post included this insightful prompt and infographic:

The trillion-dollar question: What is human judgment’s monetary value? 🤷 If a firm wants that lawyer’s know-how — to place it in an artifact (e.g., knowledge base), will that lawyer give it up for free (no additional compensation)? Especially if the lawyer is considering jumping ship — to Firm #2? Or will Firm #1 need to pay that lawyer for that scarce resource: know-how? After all, as hashtag#Tasks get commoditized (see Agents), then that lawyer’s human expertise/judgment is among the only hashtag#value left.

Damien is right to highlight scarcity. But I would frame it this way: the most valuable legal knowledge isn’t just scarce—it’s uniquely human and inalienable.

When I replied to Damien’s post, I put it simply:

“I don’t think lawyers need to worry. The truly valuable knowledge cannot be ingested by AI.”

A good discussion ensued pro and con. This article is the elaboration on my position.

The Basic Point of Disagreement

Let me start by saying I agree with Damien—up to a point. Much of what lawyers do can be absorbed and automated. The boring stuff. The repetitive stuff. The kind of tasks that make you question your life choices—zero creativity, minimal judgment required. AI can do that. And should.

I say: good riddance.

I’ve billed for thousands of hours in that rut. But the stuff I stayed for—the creativity, the improvisation, the intuitive leaps—that part cannot be transferred to AI. That’s the scarce resource. The irreplaceable trillion-dollar bit.

Let me put it this way, just off the cuff: the most valuable human knowledge in law, or in any complex domain, cannot be input into AI because it is spontaneously created on an ongoing basis by humans from out of the particular ever-changing space-time configurations. It is ever-changing. AI needs human experts. It must remain a hybrid relationship.

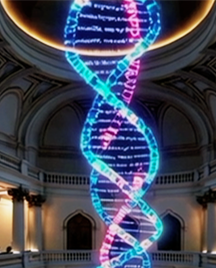

Each case, client, judge, and moment is distinct. I’ve handled a thousand legal matters since 1980, and no two have been exactly alike. None had the exact same facts, the same players, the same pressures. There are patterns, yes—but they aren’t circular. They spiral forward. Like DNA, legal reasoning evolves in loops that never exactly repeat. There’s structure, but the content within the structure is dynamic.

The best lawyers are not rote technicians—they are improvisational strategists. We may start with templates, but we do not end there. Only Gilbert-style lawyers (remember those law school simplifications?) are replaceable.

Systematic Three-Part Argument for Irreplaceability

To bring structure to this argument, I called in two of my favorite collaborators: old ChatGPT-4o (Omni) for wordsmithing, and the new state-of-the-art SORA for image generation. I prompted, shaped, edited, and reimagined—then fused their outputs with my own reasoning. That process itself is a case in point: Human-AI collaboration where the human has final control. Sometimes that’s not easy because AI can seem human and be hard to pin down.

1. Human Knowledge Is Contextual and Emergent

The most valuable legal knowledge is not reducible to rules. It emerges in context—during a tough deposition, in a late-night drafting session, in the moment you stand to speak, when you think on your feet to respond to the unexpected.

This kind of knowledge:

- Is not static (like statutes),

- Is always evolving,

- And is grounded in specific moments of time, place, and interaction.

AI lacks access to the now. It doesn’t live in our space-time. It doesn’t feel when a witness is off. It cannot read a room, has no empathy, intuition, or gut instinct.

What AI can do is amazing but this awareness should be balanced by knowledge of its limitations. This is the theme of the 100 + articles I’ve written on generative AI since 2023. See e.g., The Human Edge: How AI Can Assist But Never Replace (01/30/25). The writings are based on my personal use of generative AI since 2023 and long experiences as a lawyer and first user of other new technologies. There are always dangers in new technologies, but the elimination of legal practice is not one of them, not even with AGI or superintelligence.

Our intelligence is unique and dynamic. It arises anew each day like the Sun, emerging from the interplay of perception, emotion, intuition, and inspiration. AI has none of this. It is like the Moon that reflects the Sun’s light. All it can do is think.Our intelligence is unique and dynamic. It arises anew each day like the Sun, emerging from the interplay of perception, emotion, intuition, and inspiration. AI has none of this. It is like the Moon that reflects the Sun’s light. All it can do is think.tion, intuition, and inspiration. AI has none of this. It is like the Moon that reflects the Sun’s light. All it can do is think.

2. The Epistemological Limits of AI in Law

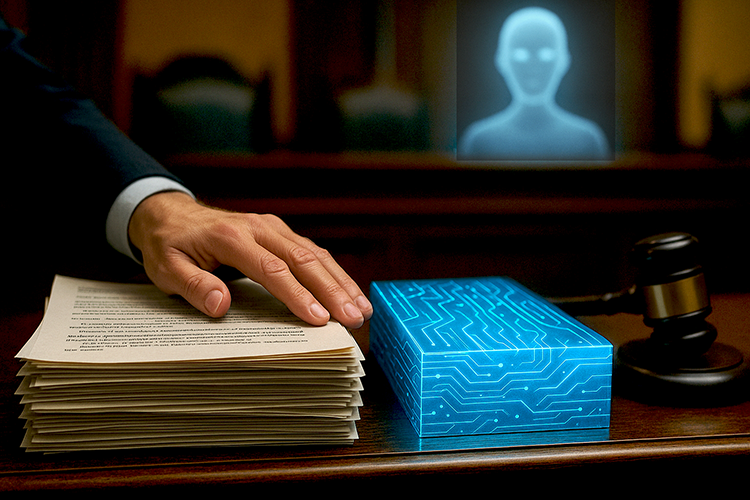

There is an boundary to what AI can know and understand. AI can simulate knowledge (e.g., predict patterns based on precedent), but it cannot originate genuine understanding or creative insight within a specific, real-world context. It lacks consciousness, lived experience, and embodied awareness—core faculties that human lawyers use to reason through complex legal and ethical challenges.

AI is like a brilliant parrot with a photographic memory—but no inner life.

I’m a strong proponent of AI, but I temper that enthusiasm with something I call ontological humility. “Ontology” deals with the nature of being, what something truly is, not just how it behaves. And that’s the key. AI may look smart and sound persuasive, but it doesn’t know anything. It predicts and correlates; it doesn’t understand or care. Judgment requires presence, experience, and agency, things AI doesn’t possess. That’s why the human must remain in charge.

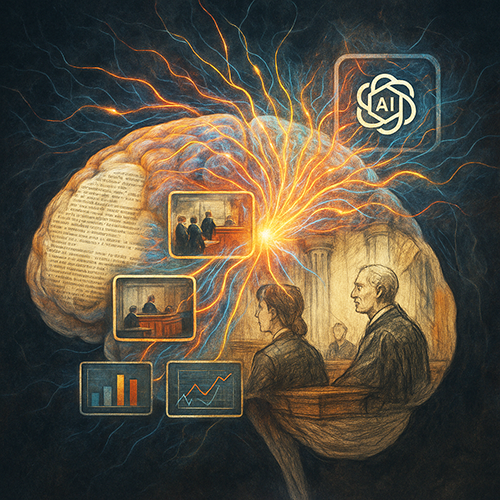

3. Hybrid Multimodal Systems: A Proven Model for the Future

Because of these limits, I have always advocated for hybrid human-AI systems. Not just in theory, but in method. Starting with e-discovery in 2012, I developed what I called Hybrid Multimodal approaches.

In that context, it meant combining:

- Predictive coding (active machine learning),

- Boolean keyword search,

- Concept search,

- Linear review,

- And—most importantly—human creativity and supervision.

Why? Because no two discovery projects are alike. And no one method suffices. The strength comes from the interplay. See the free online course I made to share the hybrid multimodal method of document review. Here is a montage of illustrations for the course prepared by Losey just using Photoshop.

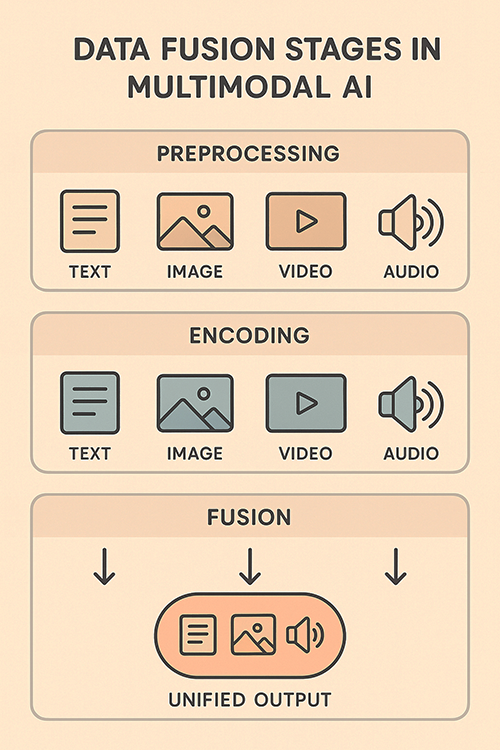

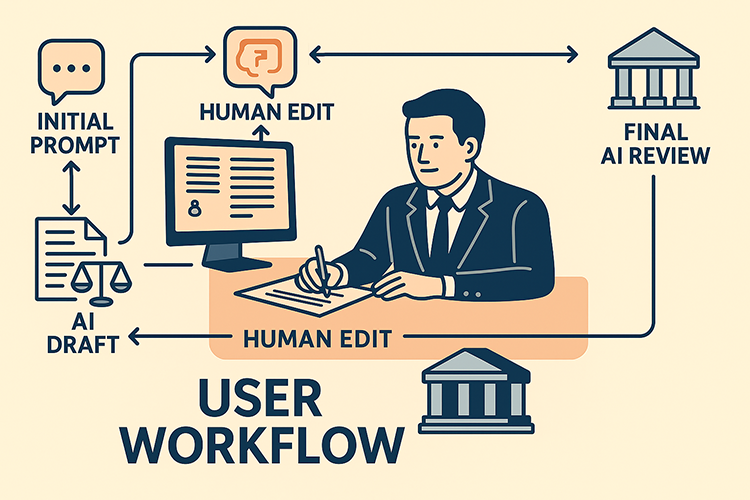

Now, in the generative AI era, Hybrid Multimodal means something broader and, for me at least, much more interesting:

- Human plus machine;

- Text plus image, plus video, plus sound;

- Prompts plus visualization, plus spontaneous human improvisation in chats; and,

- Technical, architectural design and training processes, inside the AI itself.

This last listed technical meaning of “multimodal” is new. It isn’t about how users interact with the tools—it’s about how the models are built, how they fuse the different types of data. The new AIs are designed to facilitate multimodal. Users of AI do not need to know how AI integrates multiple data types, but for the insanely curious, see the review of Li and Tang, “Multimodal Alignment and Fusion: A Survey” (arXiv, Nov. 2024) (overview of how today’s AI systems align and combine text, images, audio, and video to generate richer, more context-aware outputs.)

Below are several infographic-style images prepared by ChatGPT-4o based on the text in the last two paragraphs. They visualize what AI hybrid multimodal today means, both in the way users may interact with it and in algorithmic and training work required to fuse the data so that this is possible. These graphics thus both demonstrate this text-image fusion, and, at the same time, explain it.

Even when I already know the answer, if it’s important, I may still ask for AI input. Why? Because it sees patterns across all fields. It’s a polymath. I’m not. I use it to stretch my thinking—to see the connections I might have missed.

I know some small part of the law. AI knows everything else. That’s a powerful partnership; again, so long as we remember who’s in charge. In the future, our robots will carry the bags, just like the starting associates of old.

Conclusion

The legal profession is not facing extinction by AI. It’s facing transformation through augmentation. The question is not whether AI will replace lawyers, but which lawyers will harness AI to amplify their judgment, and which will delegate themselves into irrelevance. That is the trillion-dollar question facing all of humanity, not just lawyers.

Law’s highest-value knowledge is not static. It is situational, contextual, and alive. It emerges through human presence, experience, and discretion. No model, no matter how large, can replicate what happens in the mind of a skilled advocate adapting in real time to a novel legal problem.

AI can help us see patterns, accelerate production, and surface insights. But it cannot stand in our shoes. The future of legal excellence lies not in human replacement, but in human-AI synergy. That future is hybrid. That future is multimodal. That future is already here.

Each time you interact with advanced AI the experience is different. Sometimes what happens is surprising and leads to improvements in both quality and productivity. Click the same graphic below for a visual example.

The last words go, as usual, to the Gemini AI podcasters that chat between themselves about the article. I always prompt, and if there are too many mistakes, make them do it again. They can be pretty funny at times and have some good insights, so I think you’ll find it worth your time to listen. Echoes of AI: AI Can Improve Great Lawyers—But It Can’t Replace Them. Hear two fake podcaster talk about this article for 15 minutes. They wrote the podcast, not me.

Ralph Losey Copyright 2025 – All Rights Reserved

Assisted by GAI and LLM Technologies per EDRM GAI and LLM Policy.

[…] AI Can Improve Great Lawyers—But It Can’t Replace Them: Ralph Losey provides a thorough argument on the EDRM blog as to what AI won’t be able to do that great lawyers can. […]